Job Burton (1868-1924) was the youngest of ten children born to Samuel Burton, a blacksmith, and Jane (Hill) Burton, who resided in a small town just outside of Birmingham, England. He came to the United States with his family in 1870, settled in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, and later found employment with Arthur Kirk & Sons, an explosive manufacturing company located at Emporium in Cameron County. Burton aided in the dynamiting and clearing of debris in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, after the great flood of May 1889. Over the next decade he became an expert in the field of explosives.

In 1902, when Arthur Kirk & Sons was acquired by the E. I. DuPont de Nemours Company (or simply DuPont), he departed to start his own explosives firm. In December 1903 the Burton Powder Company, led by President Job Burton and Vice President Thomas J. Ohl, was incorporated in Pittsburgh. A handful of Burton’s relatives also joined him in the business.

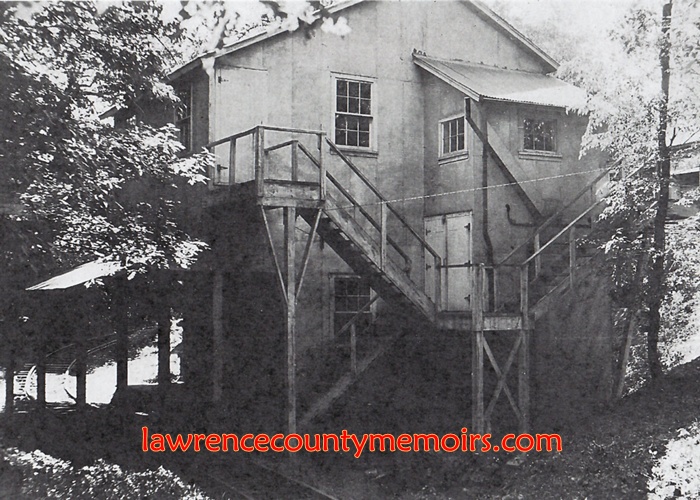

Burton acquired property just northwest of Hillsville in Lawrence County and began preparations to erect a plant. The property was along the tracks of the Mahoning State Line Railroad (MSL), being operated under lease by the Pennsylvania & Lake Erie Railroad (P&LE). It would soon be referred to as the Quaker Falls or Quakertown plant, due to a natural waterfall and old settlement located nearby, or the Lowellville plant, referring to the town just across the border in eastern Ohio.

The New Castle News of Wednesday, January 13, 1904, reported, “A new powder company is preparing to begin operations at Quaker Falls, short distance below Lowellville, says the Youngstown Vindicator. The company is known as the Burton Powder Company and when the plant is placed in operation will be one of the biggest concerns of the kind in the country. The plant will manufacture mining and blasting powder exclusively. The output will be up with that of the largest concerns in the country. Twenty acres of land have been purchased and 40 buildings are now being erected.”

The new Burton Powder Works went into operation in early August 1904. The Burton Works soon began manufacturing and supplying blasting powder for use in the mining industry, including the various limestone quarrying operations located in the vicinity of Hillsville and Bessemer.

The small plant was leveled by an explosion sometime in the summer of 1905. It would be the first of several such mishaps that unfortunately were typical in the explosives industry. The plant, soon encompassing sixty acres, was completely rebuilt, but this time – for increased safety – the buildings were erected at much greater distances from each other.

The plant was severely damaged by another explosion on Monday, April 8, 1907. The New Castle News of the same day mentioned, “One man was killed and two were fatally injured at 10:15 o’clock Monday morning by an explosion in the “corning mill” at the works of the Burton Powder company, about a mile west of Hillsville, between Hillsville and Lowellville. Jack Cain, aged about 22, unmarried and a resident of Lowellville, was instantly killed and his remains were terribly mangled.” The two men who were critically injured, Isaac Cowander and John Mackey, were transported to a hospital in Youngstown but died soon after. The explosion occurred in the corning mill, where lump explosive is passed through large rolling mills and ground into fine powder.

Burton greatly expanded his operations when a second facility, designed to manufacture sticks of dynamite, was built in a rural area south of Edinburg and along the “Bessemer Branch” of the Pittsburgh, Youngstown, and Ashtabula Railway (PY&A) – under the control of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). A spur or siding was soon built off the Bessemer Branch to serve the main part of the plant. The facility would also be served by its own narrow-gauge railroad, eventually extended to about five miles in length, which ran through two connected valleys and connected many of the distant buildings.

The New Castle News of Tuesday April 9, 1907, reported, “Work was begun Tuesday morning on the construction of a new powder works in North Beaver township by the Burton powder company. The company has purchased 50 acres of land from the Davidson heirs, and 38 from James Gilmore, thus giving ample ground for the plant. The construction will be rushed as rapidly as possible, and the industry will be in operation by June 15. Employment will be given to 50 men and 10 girls.”

The dynamite manufacturing works near Edinburg, a separate enterprise known as the American High Explosives Company, began operations in late July 1907. The plant was a bit unusual in that all the chemicals needed for production were basically made on site. Before too long hundreds of office buildings, storage warehouses, chemical laboratories, mixing houses, packing mills, munitions magazines, and safety bunkers dotted the landscape. Many of the employees of this new plant resided in New Castle and commuted by way of the passenger trains of the PRR and Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) or the “Lowellville Line” streetcars of the Mahoning & Shenango Valley Railway Company.

Veteran explosives worker George W. Van Wert (1859-1931), a native of Sullivan County, New York, helped construct the plant and would serve as its first superintendent. Job Burton had previously worked with Van Wert during his time with Arthur Kirk & Sons. Several of Van Wert’s children would also find work at the new plant, including his son Glen Van Wert who served as assistant superintendent. George Van Wert would serve as superintendent until about early 1912, at which time he would retire and be succeeded by Edward R. Day.

Business quickly boomed and the company was soon contracted to manufacture dynamite for the federal government. The New Castle News of Tuesday, April 14, 1908 reported, “A big contract for five cars of dynamite intended for the use of the United States government, has been received by the Burton Powder company which operates a large plant in the vicinity of Coverts Station. The entire order will be placed in two-inch shells, 16 inches in length.”

Another big explosion rocked the Burton Works at Quaker Falls on Saturday, August 29, 1908. The New Castle News of Monday, August 31, 1908, reported, “For the second time in 16 months the corning mill of the Burton Powder works, two miles southwest of Lowellville, blew up, causing the death of three men and the serious injury to another. The explosion occurred Saturday at 1:45 p. m., and one of the victims was killed outright, while two others died the same evening.” The three deceased men were identified as Mike Lasich, Joe Gruber, and Josef Bratkovic, while the injured man was named as George Antonio.

Job Burton reconstructed the damaged part of the plant and initiated plans to enlarge the entire operation. The New Castle News of Wednesday, December 18, 1908, reported, “Announcement has been made to the effect that the Burton Powder company of Pittsburg, which operates a 850-keg plant at Quakertown Falls in Lawrence county, near Hillsville, is contemplating a larger plant at its present site. It is reported that the capacity of the works will be doubled, and that the output will be increased accordingly.”

On Thursday, April 4, 1912, the Quaker Falls plant suffered another serious accident when a massive explosion ripped through a building housing black powder (the “press room”) and killed two men. The shock of the explosion was felt as far away as forty miles. The New Castle News of that same day reported, “One man was killed, his body being blown three hundred yards, and another was so badly burned that be died later, when the press building of the Burton Powder company, located at Quaker Falls 2 1/2 half miles east of Lowellville, was blown to pieces at 8:20 this morning. The concussion was so great that it could be heard twenty miles away, windows were smashed in homes five miles away and in this village men and horses were knocked off their feet.” The deceased men were identified as Andrew Kurzic and Mike Morris.

Two large explosions also rocked the dynamite plant near Edinburg within the next two years, but fortunately all employees escaped injury. The New Castle News of Monday, March 17, 1913, reported, “With a shock that was felt throughout the surrounding territory for three or four miles, a quantity of nitro-glycerin at the Burton Powder Works at Covert’s station, west of the city, exploded about 10 o’clock this morning. The damage done by the explosion was small, and none of the employes of the plant was hurt. According to reports from that plant the building in which the explosion occurred was the “nitrate” factory, a building about 24×30 feet and three stories in height. Something like 2,500 pounds of nitroglycerin were in the building, but much of this amount burned before the explosion occurred.”

A year later the New Castle News of Tuesday, March 11, 1914, reported, “New Castle experienced a sensation which resembled a minor earthquake when the dynamite factory of the Burton Powder company west of town let go on Tuesday afternoon. Buildings all over the city were rattled and some, of them shaking perceptibly, when the explosion demolished the dynamite factory, and the Seventh ward windows were broken in a number of buildings, the St. Charles hotel and the school building among them.”

In July 1914 active hostilities broke out in Europe and launched the conflict known as the Great War (World War I). The U. S. government took a neutral stance and tried to broker a peace settlement, but it was obvious that war was inevitable. Job Burton probably sensed a need to capitalize on the events and over the next few years he acquired several large tracts of property adjoining the plant at Edinburg. The largest acquisition, made in April 1915, was 124 acres formerly belonging to David F. Gilmore. Burton soon owned over 400 acres of land near Edinburg.

Two small explosions occurred at the Edinburg plant on New Year’s Eve, Friday, December 31, 1915. The New Castle News of the next day speculated, “The fact that this was the second explosion of unknown origin in the same day at plants of the Burton Powder company is having a tendency to give the impression that the explosions were caused by other than accidental means. It is said that the plants of that company are not engaged in the manufacture of powder and other explosives for the allies and no good reason could be assigned for attempts to blow up the plant. Reports given out indicate that the explosions are believed to be of an accidental nature.”

The operation at Edinburg was greatly expanded in early 1916. A new cluster of mills, constructed of steel and concrete, was erected about a quarter mile west of the old part of the plant. A second spur was built off of the PY&A’s Bessemer Branch to reach the new mills, which went into operation by the summer of 1916. The sprawling campus employed a force of about 300 men and had its own small fire department and police force.

Back in the fall of 1915 the Burton Powder Company, flexing its political muscle, began efforts to have the Mahoning & Shenango Valley Railway Company reduce its streetcar rates for Burton employees residing in New Castle. The City Council got involved and engaged with the Public Utility Commission (PUC) in Harrisburg. It was no small feat when in April 1916 it was announced that the one-way fare would be reduced from fifteen to ten cents. It was in the benefit of the City Council to get this measure pushed through to keep the Burton employees from moving closer to Edinburg.

An editorial in the New Castle News of Saturday, April 15, 1916, mentioned, “From a comparatively small industry the Burton Powder works at Covert’s station has grown into a big enterprise employing nearly 300 men. Most of these employes live in New Castle. The decision of the traction officials to sell a ticket costing ten cents from any part of the city to Stop 48 is a boon indeed. It means a saving of ten cents a day to all those who are obliged to ride on the street cars to the traction depot where they take the Youngstown car for Stop 48.”

A terrible tragedy struck the plant when Dr. Floyd L. Van Wert, the company physician at the Edinburg plant, was killed in September 1916. The New Castle News of Monday, September 18, 1916, reported, “Covert’s Crossing, which has been the scene of so many fatal accidents, claimed another life Monday morning, when Dr. F. L. Van Wert of 29 North Mercer street, one of the best known young physicians in the city, was instantly killed, being struck by a fast passenger train on the Pittsburg & Lake Erie railroad. The fatality has proved a terrible shock not only to his family, but to his hundreds of friends… Floyd L. Van Wert was about 33 years of age, and was one of the rising young physicians of the city. He had spent nearly all his life in this city, and was a son of Mr. and Mrs. George Van Wert, who formerly resided on Neshannock avenue, and moved but recently with their family to Emporium. The father was for years superintendent of the Burton Powder company plant.”

In early 1917, with war against Germany looming on the horizon, the Burton Works offered its full support to the U. S. government. Before too long the firm was contracted to manufacture several million pounds of T.N.T., an explosive much more stable than dynamite, to support the American military effort. On April 6, 1917, in the wake of German submarine attacks on American shipping, the U. S. government officially declared war on Germany. An editorial in the New Castle News of Monday, April 16, 1917, remarked, “With several million pounds of explosive to manufacture for Uncle Sam, the men at the Burton Powder company are now doing their bit toward overthrowing the kaiser.”

In the fall of 1917 the two Burton plants were acquired by the Grasselli Chemical Company, founded back in 1839, and merged with another company to become a new division known as the Grasselli Powder Company. Grasselli also owned a chemical plant on Sampson Street in New Castle, which supplied chemicals to the powder works. Job Burton took control of the Grasselli Powder Company from its headquarters in Cleveland, Ohio. Frank “Fritz” Harlan soon took over as plant superintendent.

The New Castle News of Monday, August 13, 1917, reported, “Entrance into the field of manufacturing high explosives became known Saturday when a new company was incorporated at Columbus, Ohio, under the name of the Grasselli Powder Company. The new concern will take over the American High Explosive Company and the Burton Powder Company of New Castle, and the Cameron Powder Manufacturing Company of Emporium, Pa. The president of the new company will be Job Burton of Pittsburg, now president of the Burton Powder company.” A subtitle of the article’s main headline read, “Not Formed As War Concern, But Government Patronage Is Assured.”

Job Burton soon left the company and took up residence near Pittsburgh. His nephew Joseph S. “Joe” Burton Sr. (1883-1978) took over management of the Grasselli Powder Company. Joe Burton had been associated with his uncle Job for about twenty years and was poised to succeed. The Burton Powder Works near Quaker Falls was soon closed and the property was later sold.

Job Burton, at the young age of fifty-six, passed away in 1924. The New Castle News of Monday, June 30, 1924, reported, “Word has been received here of the death of Job Burton of Ingram, Pa., former president and general manager of the American High Explosive company, now the Grasselli plant of this city which occurred Sunday afternoon at 1 o’clock in the Youngstown hospital. Mr. Burton was enroute from his home to Cleveland to visit his nephew when he was taken suddenly ill and was removed from the train in Youngstown. He is survived by his wife and a brother. Funeral services will take place Tuesday at 8 p. m, from the residence in Ingram, Pa.”

In December 1928 the DuPont company acquired the assets of the Grasselli Chemical Company. DuPont wasted no time in shutting down the explosives plant at Edinburg. The equipment was sold off and the many of the buildings were dismantled. The property was soon sold (or leased) to O. H. P. Green, a longtime alderman in New Castle who was involved in real estate ventures. DuPont concentrated its efforts mainly on chemical production and the chemical plant in New Castle remained in operation.

Joe Burton immediately parted ways with DuPont and spent about a year living in France. He soon returned to Pennsylvania with a plan to start a new explosives company. He rounded up a team of trusted associates that included L. F. Weitz, Frank “Fritz” Harlan, M. S. “Miff” Kinkaid, E. P. Ohl, Fred J. Burton, and A. Stanley Fox. In August 1930 he purchased, with the assistance of New Castle-based attorney Roy M. Jamison, the 400-acre abandoned explosives plant in Edinburg and established Burton Explosives Inc.

Fritz Harlan took the lead in construction efforts as the abandoned plant was quickly rebuilt on a much larger scale. The plant was rushed to completion and put into operation in January 1931. Paul Forcey took over as plant superintendent. 120 employees were hired to produce dynamite and other blasting agents for the construction and mining industry. The plant began producing a wide variety of explosives and quickly became a renowned leader in its field. The operation was able to survive the tough times of the Great Depression as its products were still sought after in the mining industry.

In July 1934 the Burton Explosives plant was acquired by the American Cyanamid & Chemical Corporation and rebranded as the Burton Explosives Division of that company. Burton oversaw the new division from headquarters in Cleveland. The plant in Edinburg was greatly enlarged until it eventually encompassed 525 acres in North Beaver and Mahoning Townships and employed about 250 workers. The parent company, with a greatly diversified portfolio of companies under its umbrella, grew to include about seventy plants around the world.

In about 1938, after an internal reorganization, Joe Burton Sr. left the company and sought employment elsewhere. The proud name of “Burton” was soon dropped and the plant was referred to as the American Cyanamid & Chemical Company.

The Edinburg plant suffered more explosions in the coming years. On Tuesday, November 12, 1940, a large explosion did little physical damage to the plant but resulted in the death of three workers – Lee Waddell, Elmer Kliduff, and Harold Duncan. The incident, coupled with explosions at several other such facilities in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, brought about suspicions of sabotage and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) became involved. Security was ramped up as the United States was a year away from entering the active throes of World War II.

In the early 1940’s the Edinburg plant remained busy manufacturing explosives for the U. S. government. The trend continued after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the United States officially entered World War II. During the conflict the plant at Edinburg, surrounded by a high fence and patrolled by guards, employed over 350 male and female workers. American Cyanamid, the New York-based parent company of the explosives plant, experienced tremendous growth as its pharmaceutical divisions supplied various vaccines, anti-toxins, and blood plasma to the American military.

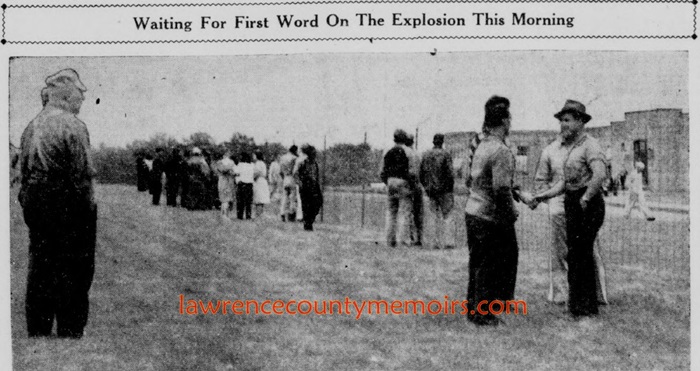

In August 1946, after further corporate restructuring, the explosives plant became known simply as American Cyanamid. Less than a year later two explosions rocked the plant on the morning of Monday, June 2, 1947, resulting in minimal property damage but killing three employees – Merle Craven, Robert Downing, and Jack Cameron – and injuring eight others. The initial explosion occurred in the jelly mixing house at 8:35am, while a second explosion leveled the dynamite mixing house a while later.

While nearby Edinburg was spared, the blast seemingly did more damage in distant New Castle. The New Castle News of Monday, June 2, 1947, reported, “There were a lot of frightened people in South Mercer street this morning about 8:40 (including the writer of this yarn). As the second explosion at American Cyanamid took place about 200 people spread out in all directions. The crowd was attracted to the new Penn hotel when the first blast took out a seven by sixteen feet plate glass window. As they stood there discussing what caused it, the second louder blast boomed out. It sounded as though it came from the back of the hotel and apparently the folks thought part of the building would be parked in their laps. They moved out as though some one had tried to take up a collection.”

Another devastating explosion, which leveled the ammonium nitrate building on Friday, December 28, 1956, killed chemist Orrin Calderwood and injured several other employees. The plant had experienced its share of mishaps and explosions over the years, but the most disastrous event was yet to come.

At 10:30am on the morning Monday, July 6, 1964, a massive explosion on the “jelly line,” where gelatin dynamite was manufactured, rocked the entire facility. Frantic employees scattered and literally ran for their lives. Two more explosives soon followed and ripped a path of destruction through the valley containing the ¾-mile-long jelly line. The explosions sent flaming debris flying in all directions and started numerous fires. Five buildings were leveled and a company locomotive, operating along the narrow-gauge railroad, was completely demolished. A fourth explosion took place at about 11:27am. The tremendous blasts were felt all throughout Lawrence County, and windows were broken in distant locales such as Mount Jackson.

Local authorities quickly went into crisis mode. The local Civil Defense team set up a command post outside the Municipal Building in New Castle. All off-duty and auxiliary policemen were called back to duty. Medical personnel at Jameson Memorial and St. Frances Hospitals in New Castle were put on alert. Fire Departments from all over the county began responding to the scene.

Emergency personnel had a tough time getting to the plant as the roads became clogged with traffic as curious people rushed to the area. The entire region was soon cordoned off by officers of the New Castle Police Department and the Pennsylvania State Police, aided by numerous auxiliary police officers. Several main roads out of New Castle were closed to traffic to keep the roads clear for medical personnel. The residents of the neighboring areas were also evacuated for their safety.

Firefighters were finally allowed into the facility at 1:00pm and took several hours to contain the various fires. The disaster could have been much worse as in the afternoon firefighters and plant personnel were able to contain a fire that threatened a magazine containing about 10,000 pounds of T.N.T. Police and fire department personnel helped pull injured victims from the carnage, as ambulances lined up to transport them to hospitals in New Castle. Red Cross and Salvation Army units set up stations to help provide medical aid, food, and water to the victims and emergency personnel. By the end of the day five of the 250 employees remained unaccounted for. Fireman remained on scene overnight to watch for any smoldering fires.

The New Castle News of Tuesday, July 7, 1964, reported, “Five workmen were presumed dead after a series of explosions created a valley of destruction yesterday at the American Cyanamid Co. near Edinburg. Searchers today probed through rubble in efforts which started yesterday amid a death-like quietness, gently lifting smoke and shattered buildings. Sharp odors of burning wood and powder along with twisted railroad rails and splintered trees created a scene resembling a war time battlefield.” The origin of the blast was believed to be in Jelly Stuffer House #1, where most of the missing men had been working. The exact cause would never be determined.

The same article listed those presumed to be dead as “Eugene Rudesill, 45, of New Castle RD 7, a gelatin packer. Gerald Wingard, 30, of 1311 Mt. Jackson Rd, a gelatin packer. Donald Schenker, 38, of Pulaski RD 1, a gelatin shoveler. Wilbur Robison 49, of 1238 Randolph St., a caser. Clarence Claypool, 63, of 754 Arlington Ave., a locomotive operator. Four of the men were working in Jelly Stuffer House, while Clarence Claypool was operating a nearby locomotive. County Constable Patsy DePrano, who assisted in the rescue effort, suffered a fatal heart attack and brought the death toll to six.”

The New Castle News of Wednesday, July 8, 1964, reported, “Five employees of American Cyanamid Co., missing since the plant was rocked by a series of explosions Monday, were officially declared dead by Lawrence County Coroner John A. Meehan Jr. Meehan issued his statement after search parties found bits of human remains in the blast area yesterday. Twenty-five men including the coroner and two of his deputies combed the site from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. The searchers were divided into small groups and assigned specific areas to cover.”

In November 2011 the late Eugene “Gene” Pisella Jr., who grew up in the Airport Inn at Parkstown Corners, wrote, “I remember this event vividly. I was 10 years old and living at Parkstown when that happened and it did a lot of damage to much of the area…knocking out our windows and bringing everything down off the walls. I remember seeing a large mushroom cloud over Edinburg. Authorities make Parkstown the cut-off point and set up a roadblock. In no time traffic was backed up as far as you could see in all directions. I also remember all the fire trucks and ambulances being forced to travel on the opposite side of the highway to get through. My mother and other neighbors made coffee and sandwiches for the men who would take breaks at Parkstown. Those are memories you never forget.”

The tragic events would be memorialized as one of the prominent moments in the history of Lawrence County. The plant never fully recovered and its operations were phased out as American Cyanamid, with a vast line of products, shifted away from manufacturing explosives. Most of the employees were laid off by the end of 1969. In June 1970 the remaining sixty employees began decontaminating many of the old dynamite manufacturing buildings in preparation of a shutdown of operations. The North Beaver Township Volunteer Fire Department subsequently conducted several controlled burns of those structures. The plant was finally closed in the summer of 1972 and the remaining employees were laid off. Most of the equipment and infrastructure, including the old narrow-gauge railroad cars, was either scrapped or sold. The P&YA’s Bessemer Branch, extending from Covert’s Crossing to Bessemer, was also abandoned soon after.

The property was purchased by the Bruce & Merrilees Electric Company, owned by J. Howard Bruce, in August 1972. It was later transferred to the control of the New Castle Development Corporation, a private interest group headed by Bruce and his family, with plans to transform the 525-acre site into an industrial park. The property, which interested several buyers, generally sat vacant for the time being. The valleys and hills of the sprawling property eventually became a ghost town of abandoned buildings and crumbling bunkers.

In early 1985 it was announced that SolidTek Systems, a waste management firm based in Morrow, Georgia, was planning to construct a hazardous waste disposal plant at the site. The plan met with stiff opposition from the local community. There were also issues regarding the possible contamination of soil at the site and the protection of nearby wetlands. After a lengthy struggle the company abandoned its plans in January 1990. A decade later, in early 2001, the ERORA Group of Louisville, Kentucky, explored the idea of building a natural gas-powered electric plant at the location. This effort was soon abandoned as well.

Another decade passed when in October 2012 it was announced that LS Power of St. Louis, Missouri, with the support of the Bruce family, was planning to acquire fifty-five acres of the property and build a 900-megawatt electric plant at the site. The proposed plant, to be powered by natural gas, was to be known as the Hickory Run Energy Station. In February 2013 the North Beaver Township supervisors approved the $750 million venture. A few months later the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) signed off on the plan provided LS Power commence with construction within eighteen months. In August 2014 the company, experiencing various delays, was given an extension of eighteen months. Construction is currently underway and it is hoped that the plant will go into operation sometime in 2017.

To read two short articles from mid-1907 about the Burton Powder Works about to commence operations, click on: WILL START WORK SOON ARTICLE and NOW IN OPERATION ARTICLE. To read how thieves broke into the Burton plant in November 1907 and made off with some valuable items, click on: THIEVES ARTICLE. To learn more about the enlargement of the plant in late 1908, click on: ENLARGE PLANT ARTICLE. Click here to see this “fiery” article: MAN BECOMES HUMAN FIRECRACKER ARTICLE. To read about the massive explosion at the plant in April 1912, click on: PLANT BLOWN TO BITS ARTICLE and FORCE OF EXPLOSION ARTICLE. To read about the explosions in March 1913 and March 1914, click on: FELT SHOCK HERE ARTICLE and DYNAMITE LETS GO ARTICLE. To read about the plant being expanded in 1915, click on: BIG ADDITION ARTICLE. To read about the citizens of New Castle being concerned about Burton trucks hauling dynamite through the city streets in 1915 click on: HAULING CAUSES INDIGNATION ARTICLE. To learn how the Burton plant was tapped to supply dynamite for the war effort in Europe, click on: LOCAL PLANT MAY FURNISH ‘TNT’ ARTICLE. To read about the Grasselli Chemical Company’s takeover of Burton, click on: GRASSELLI CO TAKES OVER ARTICLE.

|

|

Several of the men who assisted Job Burton in re-establishing the Burton Works in Edinburg in 1930. (Aug 1930) |

|

Boxes of dynamite and other materials were loaded on trucks like this and shipped out to local and regional destinations. (Photo courtesy of Wayne Cole) (1934) Full Size |

The dynamite pack house where some of the completed explosives were packed for shipment. (Wayne Cole photo) (1932) |

An explosion rocked the American Cyanamid facility on the morning of Monday, June 2, 1947. Nervous People wait outside the main gate to receive updates on the status of their loved ones. (Jun 1947) Full Size |

Lawrence County was rocked by an explosion that leveled the ammonium nitrate building at the Edinburg plant on Friday, December 28, 1956. Chemist Orrin Calderwood was killed and several other employees were injured. An even more powerful blast would take place eight years later. (Dec 1956) Full Size |

This map shows the sprawling American Cyanamid site near Edinburg in the late 1950’s. The yellow line is the relative track of the narrow-gauge railway that served the facility. The red arrow points to the general location of where the massive explosion took place on July 6, 1964. (1957) Full Size |

An official of American Cyanamid leads several newsmen on a tour of the carnage caused by the explosions on July 6, 1964. This photo went out on the wire for national publication. Full Size |

The five men who were killed in the horrific explosions on the morning of July 6, 1964. Claypool was operating a small locomotive, while the other four were working at or near jelly stuffer house #1. (1964) Full Size |

|

The various buildings of the hilltop area, served by railroad siding #2, of the American Cyanamid facility near Edinburg. (1960) |

(1960) |

Comments

Andrew "Drew" Burton #

I am the grandson of Joseph S. Burton Sr.

Jr. was my dad…

I have the original picture shown above of my grandfather. As well as a picture of the Burton Explosives 1st Anniversary on Jan.10,1931.

Also have a picture of Job Burton and not to be forgotten Job’s older brother Danial Burton who died in 1898 after an explosion in a tunnel when he entered too soon and was overcome by gasses.

The three of them are published in a book “The History Of Explosives In America”

I am very big into my family tree, and am very proud of my blood-line…

Drew

Betty #

My brother and my father were both working at the plant at the time of the explosion. My father was in one of the buildings that imploded. I was told that the buildings were built so that the walls would collapse and the roof would come down to smother the blast and hopefully keep it from setting off a chain reaction. The roof of his fell on top of him and he was one of the lucky ones who was only injured. The large two story brick building in the photo above was the “mix house”. The gelatin house is where the blast began. The men were inserting the gelatin into tubes/casings, much like sausage is made, pinching off the explosive and loading another tube, repeating the process. Apparently the tip of the nozzle became overheated igniting the gelatin.

Keith Fulton #

Hello, I think my father worked at this plant in the 1940’s. That might be him in the picture – the third person in from the left in the front row. His name was Everett Keith Fulton and my Mom’s name was Genevieve. They lived in New Castle where I was born in 1949. If anyone has any information about the plant or the workers I would be interested in talking to you. Thank you. Keith – Keithf4099@aol.com

John burns #

Drew,

Interesting review. It’s hard to keep all of it organized and here are the rudiments in one spot. Daniel was my great grandfather. I stumbled on a Burton Explosives box yesterday in New Oxford, PA. which inspired another research spasm.

John

Patti #

I was standing in my backyard with my children when I heard an awful sound. I immediately knew what it was. My mother worked there during the war while my dad was in service as did many women at that time. My friend, Joe Niglio, was working at the plant that day. Took a long time to get through to his wife, but we received wonderful news. He was alive. When I think of that day, I can almost feel the earth shaking under my feet, just as it did that day.

John Morris #

Grew up in Mt Jackson. We lived in Jackson Knolls at the time when the 1964 debacle occurred.I was 11 years old. But we where on the first day of a camping vacation to Arizona. The evening after the explosion, we picked up a newsapaper in Angola Indiana and it was front page national news. Neighbors later said the blast knocked them out of bed, and had the effect of an earthquake. Like previous poster said, the adults knew instantly what had occured. several years later as a teenager, I remember riding my bicycle on a dirt road that went behind the facility property and seeing some evidence of the explosion.

JOHN COVER SR. #

Jeff, thank you for all your work in this endeavor. When I saw the picture of the

American Cynamide annual picnic of 1940 I recognized the face of my Father Walter Cover who worked there. It is only one of three pictures I have of him. He died in 1952 from a home accident when I was only 8. I remember my Mother having a copy of the same photo but was never able to find it in here belongings. He is almost the true center of the photo in a sweater and has the collar out. I also remember a couple of the blasts and my Mothers concern. I have a copy of his I.D. badge if you’d like to add it to this. Again, thank you for the wonderful memory…JC

Anna Anderson #

Hi, just googled for some information on American Cyanamid and found this. My father was Donald Schenker who was killed in the 1964 explosion. My brother worked there for a short time in the late 60’s. He and I have been collecting/gathering information.

Thank you all for posting information. The Historical society is planning a 50 yr rememberance of this tragic event for April 2014. Any information you would like to share would be welcomed tremendously. My email is annamand@yahoo.com

anna anderson #

My father, Matthew Curtis was a chemist from the forties to his untimely death in 1963. My mother always said his massive heart attack was due to the work he did at American Cyanamid. Alice Curtis Palmer amp1346@yahoo.com

Carolyn Peluso #

My Grandpap worked the line that exploded, but he had retired. My mom remembers that he worked on Friday and the line blew on Monday – he was friends with all the men who were lost. The policeman who died was my Grandma’s brother – my Uncle Patsy – he had a heart attack when he heard the explosions. We have the newspaper clippings from that day. I’ll see if I can find them and I will send them to you.

Ken Wigton #

My dad Joseph Wigton worked at what we called the Dynamite Plant around 1940. He is 93 and I will ask him if he remembers when he was there. Awesome article! Ken W.

Bev Oels #

I remember it well. Sitting at my desk in the office and then rushing into the hallway away from the big glass windows and wondering how it would end. As in would I be driving home that day. Knowing that my family living on the east side of New Castle would have no need to be told what had happened and no way to call them and let them know that I was okay.

Watching as fireman were helpless to do anything to put out the fire and wondering which of the men on the lines were no longer with us.

Several days later our boss, Ed Bevin, took us on a tour down the line so we could see the devastation for ourselves. The one image I will never forget was the railroad track that had been twisted and thrown high in the trees above. That and seeing what was left – nothing- of what had once been a three story brick building.

Ken Wigton #

I spoke with my father and sent him the picnic picture. He is in the picture. He remembers it well as it was the first time he ever drank alcohol! probably made him decide not to drink as he was so sick. He said that you had to be 20 to work there but he had someone on the inside that got him in before his 19th birthday. Sadly I lost dad in August. I will have many memories of him and Edinburg and I visit there to see cousins occasionally.

Michael Woulfe #

My sister and I have been researching our ancestry for several years. We have tracked down our great grandfather as having emigrating from Italy to New Castle PA. in the 1890s. In 1899 he was working for the Syndicate Fireworks Co. Although we were estranged from this side of our father’s family, the story is he was killed in an explosion. All indications are that this happened before 1910 when the family moved to Akron OH then to St. Louis MO.

Yesterday I was researching the Library-Of Congress Archives on line. I found a small article in several newspapers dated April 8, 1907 that reports an explosion at the Burton Powder Co in a town near New Castle named Hillsvale. Three people were instantly killed. Only one person was identified. The other two were listed as “Italians”. I feel strongly he might have been one of the two unnamed.

My sister and I can find no death notice or obituary for our great grandfather. Like many immigrant of that time, we believe he went by several names. Polo Lem, Paul Lem, Leopold Lem…. But we recently believe his real name was Ippolito Lamuca.

Your site has given us a glimpse of hope. If anyone could help us with the identification of the two Italians mentioned in the accident or some verification of his death and/or the location of his remains, we would greatly appreciate it.

Thank You.

Richard J. Harvey #

My first job when I got discharged in Jun. 1957 was stripping dynamite at the Powder Plant. I only lasted a few days. The fumes made me deathly sick. I quit and within a week I went to work at Penn Power. I was working in the West Pittsburgh Power Plant on the day of the explosion in 1964. The first blast shook the whole plant. We were trying to find the source of what malfunction inside the plant caused the shaking when we were informed it was the powder plant. I immediately took the elevator to the top of the plant to take a look. I no sooner got there when the last blast when off. The mushroom cloud that went up looked like a atomic explosion, and the blast that came down that river all but knocked me down. While watching I was thanking God I had quit there 6 years before. One of my ball playing friends lost his father that day. I also had a number of friends who worked there but non were hurt.

Jeff Bales (EDITOR) #

(EDITOR’S NOTE) Michael W, I am aware of the accident that occurred at the Burton Works near Hillsville on April 8, 1907. Newspapers sometimes give out different names or spellings of the victims as the story develops, but I can tell you what I found. The New Castle News of Monday, April 8, 1907, identified the deceased as “Jack Cain, aged about 22, unmarried and a resident of Lowellville.” The two injured men, who died later that day in a Youngstown hospital, were identified as Isaac Cowander and John Mackey.

Janyth Williams #

My father, Roy C. Williams, began working for American Cyanamid as a chemist… and was eventually promoted to Assistant Plant Manager under LeRoy Clark. Dad worked at the New Castle plant from around 1939 to 1953 when Cyanamid transferred him to Linden NJ (Dad retired from Cyanamid in 1978 at age 65 and he lived to be 96). It is quite possible he is in the 1940 picnic photo in the back row on the left, but I cannot identify him with certainty.

I was 4 years old in 1947 and we were living at N. Jefferson St. & Wallace Av (at the top of the downtown hill in New Castle). One of my most vivid childhood memories was of our apartment shaking from a couple of blasts, my mother clutching the sink in the bathroom, and her telling me, “Please don’t say a word until the telephone rings”… and that did not occur for what seemed to be a long time (maybe 45 min.?). I didn’t know what had happened, but even as a small child I knew it was serious. After the phone call from Dad saying that he was okay, Mom cried for a long time… from stress, of course, and for the 3 men who were killed. Later Dad told us that he had been talking to the 3 men, and that the building exploded just after he walked out — he still told the story in vivid detail when he was in his 90’s (the recovery of human remains was quite gory).

I often heard my father refer to Paul Forcey (mentioned in the article), but I am not sure what their relationship was. It is possible that Paul is the man who hired Dad, who was fresh out of Penn State when he started in the chem lab.

Janyth Williams #

P.S. to my story above about Roy C. Williams: I recall my dad telling me about doing consulting work for the Rossi’s — apparently the 2 companies had a mutual interest in combustion. I believe Dad said he helped the Rossi’s, via his chemistry background, to intensify the colors of their fireworks… and to create a few new ones. Perhaps Lawrence Co. historians have some background about any relationship between American Cyanamid and Rossi Fireworks…?

ERNST THOMS #

A distant relative in my wife’s family died in an explosion at the Lawrence County Burton Powder Works on November 22, 1923 as listed on his death certificate found on ancestry.com

Name Asa Burton age 53 from Ohio. No relation to the company Burtons.

J. Nelson McConahy Jr. #

I am the author of the book “DYNAMITE! A Blaster’s History”. My father J. Nelson McConahy Sr.He started to work at the plant in 1939.He is in the photo of 1940. I started to work at the plant in 1965. The book is non-fiction and all the pictures and stories are true. I wrote the book to pay tribute to all the workers and their families who worked at the “Powder Mill”. I along with many others are doing our best to keep the memory of the Powder Mill alive. If I can give you any information on the Plant let me know. The book is a “must have”. for anyone who is interested in the History. Seniority lists, Pay scales, etc.

Robert A. Dunkle #

My Father worked for American Cyanamid in the mid to late 1950’s. He was involved in a fire and explosion there, this was the Azusa plant. I’m doing family history,today I’m unable to find any information on this. Would you be able to help me? Sincerely Robert A. Dunkle,I

Harold Duncan #

My father, Charles Duncan and his brother Harold Duncan worked at the powder mill from the mid 1930’s. My uncle Harold Duncan, for whom I am named, was one of the three men killed in the Nov. 12, 1940 explosion. My father was asked by the company to help search for remains after the explosion. He found an identifiable part of my uncle’s remains among the carnage. My father worked at the powder mill for a short time following the explosion, but couldn’t continue for grieving over his brother Harold. He found employment elsewhere. Thank you for continuing the research on the history of the powder mill. Its grounds are hallowed to those who lost loved ones there.

Patty Wardle #

Researching my Great Uncle Patsy DePrano lead me to this information. My parents always told me I was named after my Uncle Pat. I now understand why, he died in the month of July of 1964, the month and year I was born.

Stephen Burton Burns #

My grandfather was Charles Burton and he was also employed in the explosives business. Among other things he worked on the Pennsylvania turnpike. On the first day the turnpike opened, people were lined up at the tollgate waiting to be amoung the first to drive on it, and my grandfather was in the group. A newspaper reporter asked, “Mr. Burton, how long have you been waiting to get on the turnpike?”. To which my grandfather answered “Ten years.” (This story told to me by my mother Gladys Burton Burns when I was a small boy)

Comment