On Monday, March 11, 1918, in the midst of the Great War (World War I), a U.S. Army private named Albert M. Gitchell checked himself into the infirmary at Fort Riley, Kansas, complaining of a sore throat, headache, and fever. By the end of the day over a hundred of his fellow soldiers were also ill with identical symptoms. The men were all suffering from a new strain of the Influenza A virus known as H1N1, later known popularly known as “swine flu” due to its prevalence among pigs. The outbreak at Fort Riley quickly spread and when it was finally under control by the end of April 1918 a reported 1,127 soldiers were sick and 46 of them (but not Gitchell) had died.

Fort Riley was one of the initial hotspots of this extremely contagious strain of influenza, but its actual location of origin is still debated today. Other military installations in the United States experienced similar outbreaks, and before too long infected troops being sent “Over There” brought the sickness to the front lines of wartime France. The flu quickly afflicted all of the war-torn countries of Europe, and then began to spread throughout the entire world.

Wartime censorship actually hid the news from the general public for a few months. It wasn’t until late May 1918 when the newspapers in the neutral country of Spain, where King Alfonso XIII was gravely ill with the flu, reported on the pandemic and made it an international story. It was these reports that led to the outbreak, although it did not originate in Spain, being dubbed as the “Spanish Flu.” It was also known by the French phrase “La Grippe” (The Grip).

The outbreak took some time to spread, but was generally over by the late summer of 1918. At this point the extremely contagious Spanish Flu was a serious medical concern, but was not particularly deadly. However, like most flu outbreaks, it would strike in several waves and the next wave would afflict the world’s populace like never before or since.

In mid-September 1918 the city of Boston, Massachusetts, (and a few other locations in France and Africa) began to suffer from a new wave of the Spanish Flu. The influenza had obviously mutated and this second wave was marked by an unusual feature: An extremely high mortality rate, especially among healthy young adults aged 15-25. Almost 4,000 Bostonians died from the respiratory illness in the next month, and before too long the entire country was under siege from the deadly influenza bug.

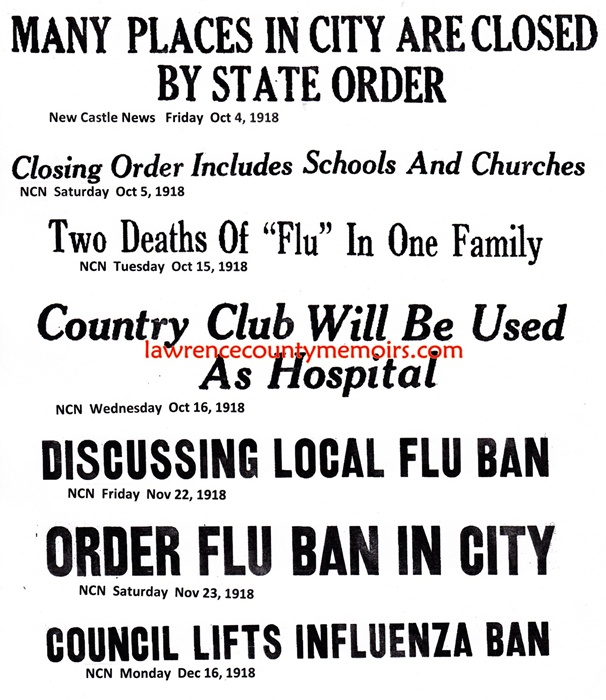

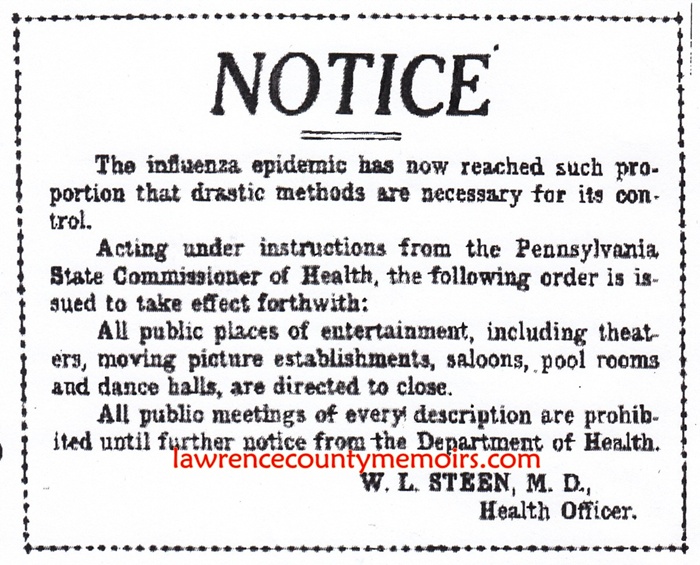

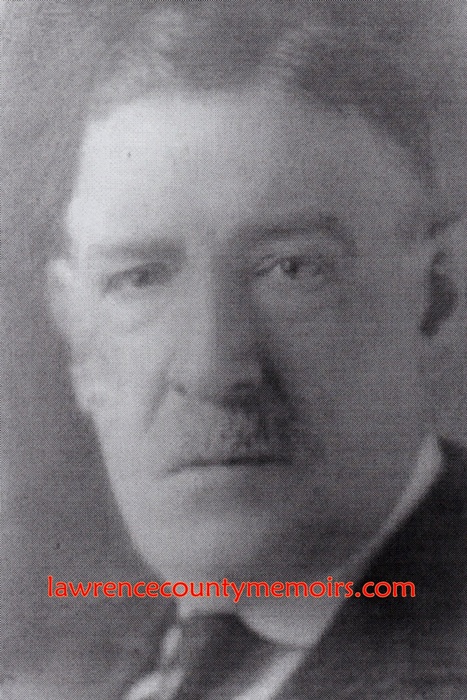

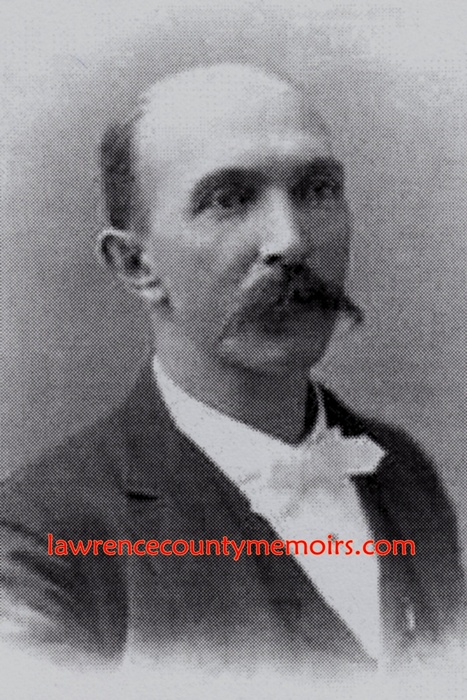

In early October 1918 the first reported cases of this second wave of Spanish Flu began to hit New Castle, Pennsylvania. Mayor Archibald D. Newell, the City Council, City Health Officer Dr. William L. Steen, City Physician Dr. James K. Pollock, and County Coroner Elmer P. Norris began meeting to come up with a plan of attack to fight the local epidemic. Dr. Steen, a University of Pittsburgh graduate who served as the City Health Officer from 1915-1943, led the effort until he was departed in mid-November 1918 to serve with the U.S. Army. The seventy-three-year-old Dr. Pollock, a well-known and prominent local citizen, became acting Health Officer in Steen’s absence.

An unprecedented “Flu Ban” went into effect on Friday, October 4, as all schools, churches, theaters, saloons, wholesale liquor stores, billiard rooms, dance halls, fraternal lodges, and other public meeting places were closed until further notice. Sick persons were ordered quarantined in a separate room in each afflicted house. An “anti-spitting ordinance,” backed by a $1 fine and a possible short jail term, was enacted to authorize the police to arrest anyone caught spitting in public. Other measures included limited attendance and a quick pace at weddings and funerals, a discouraged use of public transportation, staggered employee hours at large factories, and the mandatory reporting of all cases of illness to the City Health Officer. Retail businesses were allowed to remain open, but people were warned to exercise caution when shopping.

Sunday, October 6, 1918, was reported to be one of the quietest days in the history of New Castle. That day was already a “Gasless Sunday,” a wartime initiative to save gas and support the military effort in Europe. Now with all city churches ordered closed for the first time ever the downtown area was literally deserted. Most residents simply sheltered in their homes hoping to avoid the Spanish Flu.

The most serious patients were admitted to the Shenango Valley Hospital on North Beaver Street, which was quickly filled to capacity. On Wednesday, October 16, the City Council decided to set up an emergency hospital at the New Castle Country Club (or Field Club) along Vine Street in the Croton area of the city. At this time there were a reported 242 cases of the Spanish Flu in the city and the American Red Cross joined the fight. Upon approval of Dr. Steen, the City Health Officer, any physician could admit a patient to the emergency hospital at a cost of $1.50 a day. The Red Cross, augmented by hundreds of local volunteers, ran the hospital and other outreach programs.

By the end of October there were a reported 864 cases of influenza in New Castle. Most of those were concentrated on the East Side and South Side sections of the city, with a few isolated cases in Mahoningtown (mostly with transient railroad men) and on the North Hill. The West Side was fortunate and remained almost free of the Spanish Flu. Afflicted persons were quickly overwhelmed with chills, fatigue, headache, high fever, and delirium. Many of the afflicted coughed up blood and developed cyanosis, a bluish discoloration of the skin. A small percentage died within a day or two of feeling ill and those that survived often developed aggressive forms of pneumonia or tuberculosis.

Ellwood City also faced a similar crisis and had a reported 555 cases of Spanish Flu by October 28. An emergency hospital was established at the old Polish Club building at Crescent Avenue and Tenth Street. In late November the influenza began spreading into the neighboring areas of North Sewickley Township, Frisco, and Wurtemburg. With New Castle and Ellwood City locked in a struggle it was almost impossible to assist the outlying communities throughout Lawrence County. Wampum (and the neighboring locales of Clinton and Coverdale) was probably the worst off of all the smaller villages in the county. The Crescent Portland Cement Company, assisted by the Red Cross and local volunteers, took the lead in battling the outbreak in that area. Others areas facing a substantial number of influenza cases included West Pittsburg, Bessemer, Hillsville, New Wilmington, and Volant.

The medical community was ill equipped to meet the threat and treatments did almost nothing to help. Several new or existing vaccines were being tested, but without a real understanding of the causes of the flu they were ineffective. Doctors were relying on techniques learned during the large scale influenza outbreak back in 1889-90. It wasn’t until the 1930’s that researchers, learning that influenza was caused by a virus vice bacterium, began making strides to develop a successful influenza vaccine. The situation in 1918 was made worse by the fact that many of the nation’s qualified medical personnel were off serving in the military. And they would be needed because of the 117,000 total deaths suffered by the U.S. military during World War I, about 43,000 of those succumbed due to complications from the Spanish Flu.

What did work was a host of preventive health measures such as advocating the wearing of gauze masks, quarantining sick patients, and closing public meeting places seemed to stem the tide of the outbreak. Many people also devised their own home-grown remedies, which often included the use of onions. An article in the New Castle News of October 20, 1918, advised that the Reverend Wilbur G. Volivia, a famous Zion evangelist, advised people to eat onions because “No germs like onions” and “besides if you eat onions people will stay away from you and that is important in checking the influenza epidemic.” Alcohol was also believed to help, but with saloons and wholesale liquor stores closed it was hard to come by.

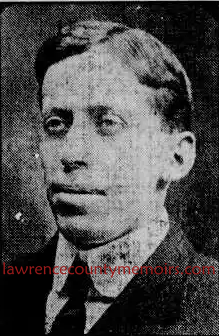

On Monday, November 4, there were a reported 1,019 cases of influenza in New Castle, though the outbreak was largely under control. A high-profile local casualty took place on the evening of Thursday, November 7, when forty-eight-year-old County Coroner Elmer P. Norris, who survived a bout with the influenza, died at his residence on North Jefferson Street due to complications from flu-related pneumonia. A few days later, on Sunday, November 10, the flu ban in New Castle was lifted and all schools, churches, theaters, and other public meeting places were reopened. This would prove to be a costly mistake.

The next day the headline of the New Castle News read, “IMPOSSIBLE FOR HUNS TO RESUME WARFARE,” while a sub-headline announced, “BIG WORLD WAR COMES TO AN END AT 6 A.M.” The Armistice officially ended the hostilities in Europe and local citizens, already relieved by the end of the flu ban, were excited to read all about it. Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, proved to be a complete disaster. As expected local citizens poured into the streets to celebrate, mingling with strangers, hugging and kissing each other, and sharing cigarettes.

There was a brief lull, but after a week or so the Spanish Flu was back in full force. On Friday, November 22, city officials met for hours to decide what action to take. They enacted a new flu ban, this time with more stringent measures, to commence at 6:00 p.m. the following day. At noon on November 23 it was reported that ninety-five new cases had been reported in the last twenty-four hours, bringing the total since early October up to 1,956 cases.

The new ban once again closed schools, churches, and all other public meeting places, but also placed severe restrictions on street cars. Street cars officials were ordered to carry only a limited number of patrons at one time, keep the windows open at most times, and to clean the interiors of the cars on a regular basis. Notices were placed on the front doors of homes where sick people were quarantined advising, “Spanish Influenza, stay out, by order of the Board of Health.” Citizens were also warned about the dangers of kissing, urged to use their own dedicated eating utensils, and reminded to keep their fingers out of their mouths when in public.

Prominent civic leaders meet with city officials on Wednesday, December 4, 1918, to discuss the situation. Businessman George Greer, who founded the tin mill industry in New Castle, was selected to head up a committee to explore ways the public could assist the official effort. O.J.H. Hartsuff, an executive with the Carnegie Steel Company, served as chairman of a Red Cross fundraising drive from December 16-24.

The Red Cross Emergency Hospital at the Country Club, suffering from a lack of heating and also proper sanitary facilities, was moved to the larger Knights of Columbus home on North Jefferson Street on the evening of December 4. The Red Cross soon set up a command center in the Masonic Lodge on North Street, and later moved to the Safe Deposit and Trust Company building on North Mercer Street in March 1919.

The influenza outbreak was soon brought under control and the second flu ban was lifted on Monday, December 16. Churches and other public meeting places were authorized to reopen, but public and parochial schools were to remain closed for another few days. Churches were reopened just in time for holiday services.

The New Castle News of Thursday, January 9, 1919, reported, “The influenza epidemic is believed to be a thing of the past if the health reports may be taken as the basis of such an opinion.” The same article also pointed out that no new cases had been reported in the last three days. A third wave of the Spanish Flu struck in the early months of 1919 and periodic cases were reported in New Castle until the early summer. The Spanish Flu continued to rage in other regions of the world, but basically ran its course by the fall of 1919.The United States suffered 675,000 total deaths from the Spanish Flu and Pennsylvania was hit particularly hard. During October 1918 the state suffered a reported 28,505 deaths from the flu, 8,433 from pneumonia, and 1,379 from tuberculosis. A large portion of those deaths occurred in Philadelphia, where officials were slow to respond to the influenza threat and were saddled with the worst rate of death among all cities in the United States.

Lawrence County was more fortunate and actually suffered relatively few deaths when compared to other areas. There were a reported 2,801 cases of the Spanish Flu in New Castle from October-December 1918, with 212 cases resulting in death. During that same period Ellwood City had a reported 1,543 cases with 48 deaths. The numbers can be deceiving because in Ellwood City another 69 people died from flu-related pneumonia or tuberculosis. The Borough of Wampum was probably the worst off in terms of percentage, suffering almost 900 cases of the Spanish Flu with a reported 37 deaths.

Getting an accurate worldwide count can be difficult, but modern research estimates that at least 50 million people – but maybe as many as 100 million – died from the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919. When it was all said and done it’s possible that about 6% of the world’s population had died. Just when and where the Spanish Flu originated is still debated today, but there is no debate that is was one of the greatest medical disasters of all time. It wasn’t until the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-2022 that the world witnessed anything even similar.

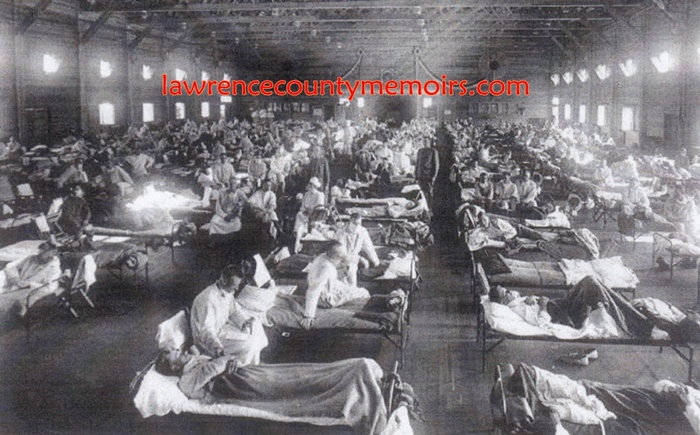

The first large outbreak of the Spanish Flu occurred in March 1918 at Fort Riley, a sprawling U.S. Army training facility located in north central Kansas. Over 1,100 soldiers fell ill and were hospitalized at Fort Riley (shown above). Similar outbreaks followed at other military bases and this has led many people to believe the flu was a product of the U.S. military’s biological warfare effort. In March and April 1918 as many as 202,000 American troops were sent to join the war effort in Europe. They carried more than their gear – they carried the Spanish Flu as well. (1918) Full Size |

|

A typical emergency hospital prevalent in 1918, this one on the porch of the U.S. Army’s Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. Isolation and ventilation were thought to be key factors in treating the Spanish Flu. Bed sheets were used as sneeze guards between the patients. This scene was commonplace throughout the world, as isolation wards were set up in hospitals, churches, factories, private homes, and other buildings. (1918) Full Size |

The emergency hospital setup on Church Street in Wampum in September 1918. Wampum, and surrounding areas like Crescentdale, Clinton, Coverdale, were hit hard by the Spanish Flu with a reported 885 cases – with 37 deaths. The Crescent Portland Cement Company also set up an emergency hospital for its employees. (1918) Full Size |

A popular children’s historical rhyme that originated during the time of the Spanish Flu epidemic in 1918. Full Size |

On Friday, October 4, 1918, Dr. Steen ordered that this notice be posted on all dance halls, saloons, wholesale liquor stores, theaters, and other public meeting places. Schools and churches were soon added to the list of places to be shuttered. This notice signaled the beginning of the first “flu ban” in New Castle, which lasted until November 10. (1918) Full Size |

Comments

Joneta Burke #

Excellent article Jeff.

GAIL (BLOSZ) HIGHTREE #

My grandfather, Ignatius Blosz, succumbed to the swine flu epidemic on July 2, 1919. He is buried at St. Joe’s. I’m soon going to take a trip there to find his stone.

Comment