This is a test.

Welding Fittings/Flowline Corporation - Shenango Twnp PA

|

|

|

|

This is a test.

Text Coming Soon!

In June 1946 former U.S. Army Air Forces (AAF) pilot Frank J. Farone (1915-1996), a pharmacist by trade, was authorized to build a training field for pilots in Shenango Township. The small airfield, located along the New Castle-Ellwood Road, was known as “Port Shenango” and opened in October 1947. The airfield was in operation just a short while before being closed by early 1950. Farone went on to have a longtime connection with the New Castle Airport in Union Township, and eventually served on the board of the New Castle Airport Authority from 1970-1985. The former airport site in Shenango Township was converted into a school athletic field (as shown above) in 1953. Several years later the property was acquired to became the home of the Lawrence Village Plaza, a shopping center that opened in 1961. (1958) Full Size |

Text Coming Soon!

Local children adorned in traditional Polish attire pose in front of the old Polish Club in Chewton. (1943) (Courtesy of Barbara Hoziak Hairhogger) Full Size |

Children take part in a stage production at the Polish Club. (c1943) Full Size |

(c1943) Full Size |

(c1943) Full Size |

At about 10:15pm on the night of Saturday, January 7, 1899, seventy-year-old John Blevins, the well-known City Treasurer of New Castle, Pennsylvania, went to his office in the City Hall building. When he failed to return to his residence by midnight his son William “Bill” Blevins went looking for him. What the younger Blevins found in the City Treasurer’s office became a tragic and sensational news story.

John Blevins was born in Ireland in 1828 and came to the United States with his parents when he was three years old. His family settled in Washington Township in what later became Lawrence County. When he was seventeen he was made his way to New Castle and took a job with a local tailor. In 1850 he was married to the former Ruth Thorne and together they had several children. He later started his own grocery business. In 1884 he ran for City Treasurer and was defeated by Robert Osburn, but was elected the next time out a year later. “Uncle John” was reelected several times and became a popular figure in New Castle.

The evening of Saturday, January 7, 1899, was very cold and the streets and sidewalks were covered with ice. Blevins, as usual, spent a good portion of the day in his office on the first floor of the old City Hall. The building was located at the foot of the Pittsburg Street Bridge (East Washington Street Bridge), at the corner of East Washington and East Streets. His office was accessible from a main entrance on East Street, and was located across the hall from the office of Mayor Samuel W. Smith.

In the early evening local plumber Adolph Stadler, wanting to cash a check, visited Blevins in his office to do so. Afterwards, Blevins went home to his nearby residence on North Street and had dinner with his wife Ruth. He then returned to his office and was visited by his close friend a businessman Perry Douds, a former Lawrence County Deputy Sheriff and local civil servant. Blevins left the home at 9:00pm to go to a local tailor shop to check on alterations being done to an overcoat. Learning the work was not yet completed he visited his son William “Bill” Blevins, employed in a nearby shop, and then returned to his office around 10:15pm. Exactly what happened next remains a mystery to this day.

At about 11:30pm his son went to the Blevins family residence on North Street and learned his father had not returned home for the evening. He immediately made his way to City Hall and arrived just after midnight. He found his elderly father lying partially face down in a pool of blood under his desk. The room was in a state of distress and blood splattered the immediate area. He sprinted to the neighboring New Castle Fire Department on East Street, where Frank J. Connery (the future Fire Chief from 1901-1924) and Frank Vandergrift came to assist. He then alerted Dr. James K. Pollock, who arrived just in time to witness Blevins gasp his last breath. Police and other city officials soon arrived on scene. As news of the dastardly murder quickly spread, a large crowd of people gathered on the street outside.

Blevins, his private office in disarray, had obviously put up a desperate struggle as blood splattered the immediate area – on the desk, chairs, and book shelves. He had received a series of savage blows to his left temple and head, had a severely crushed nose, and a dislocated jaw. It appeared a heavy, sharp instrument had been utilized as the murder weapon. Blevins’ body was soon removed to the Dunn & Rice undertaking home, where City Coroner Edmund C. Porter, a veterinary surgeon by trade, and several doctors took up a thorough examination of the remains. Blevins had over a dozen major impacts on his head and face, and a crushing blow to the back of his skull was thought to have led to his death.

The next morning at 11:15am a slew of city and county officials gathered at City Hall to conduct a thorough examination of the bloody crime scene. Robbery seemed the motive as a small vault, with several lock boxes, had been pried open and its contents were missing. Saturday would be the most opportune time to rob the City Treasurer, because banks closed early that day and Blevins would probably have extra cash on hand. It’s unknown how much cash was contained in the vault, but it was thought to be about $500. Blevins’ pockets had been emptied as well.

It seemed likely that the crime was committed by more than one person. Blevins either walked in on the robbery attempt at about 10:15pm, or he was already in his private office and the intruders came in and surprised him. Blevins blood-soaked keys were found in the lock on the inside of the door. It appeared that after they beat him, they took his keys and locked the door from the inside while they emptied out the safe. Some people speculated Blevins may have actually known his assailants. Oddly enough, a strip of heavy iron was found in a basin of water within the office, but it was not a match for the wounds. A bloody handkerchief was also found. A large tax book was opened, as perhaps the assailants came in and pretended to want to pay their taxes. It was also reported that some of Blevins’ paperwork or books may have been stolen as well. No substantial clues were located as the intruder or intruders apparently covered their tracks quite well.

The Police Department and city jail were located directly below Blevins’ office and several inmates (who were unattended at the time) said they had heard a brief shuffling the previous night. No screams or cries for help were heard though. A dozen policemen had been on duty, but they were all out on the street and walking the beat. It seems the vicious struggle lasted a few minutes or more.

Local police officials, led by New Castle Chief of Police William McClain and County Detective Stephen B. Marshall, took up the investigation. Policemen took to the streets and began questioning suspicious persons. Four homeless men were arrested on Sunday, as it was initially speculated that vagrants might be responsible. The “tramp theory” was quickly discounted as the crime seemed to be more of a well-planned operation vice an act of desperation. The citizens of New Castle were in shock, as it appeared the police had little to go on.

On Monday, January 9, a reward of $4,000 was announced for the capture of the assailants, as the City Council and County Commissioners each chipped in $2,000. The next day a solemn funeral service was held for Blevins at the First Presbyterian Church.

The New Castle News of Wednesday, January 11, 1899, reported, “Never in the history of New Castle has the funeral service of any citizen been so largely attended as was that of City Treasurer John Blevins, on Tuesday afternoon. The First Presbyterian church, the largest in the city, was crowded to its utmost capacity, and many turned away, unable to gain admittance. At 1 o’clock the remains were removed from the family residence on North Street to the church. They were encased in a handsome black casket. At the church the casket was placed in the vestibule of the church, being arranged that the people could pass by on either side. Until 2:30 o’clock, the hour fixed fur the funeral services, the remains lay in state, and were viewed by thousands. The street, for a block either way, was crowded with people… At 2:30 o’clock the church was filled to overflowing. At about that hour the city officials, city councils, police force, paid employees of the fire department, and the school board filed into the church and took seats reserved for them. The family and relatives came in later…The services were opened by a selection by a quartette, after which Rev. T. W. Winter led in a short prayer. Dr. (M. H.) Calkins read several scriptural selections, after which Dr. (R. A.) Browne arose and made a brief address… Rev. J. Q. A. McDowell then delivered an address… At the conclusion of the services the remains were placed in the funeral car and the funeral procession was formed and weaved its way to Greenwood cemetery. There, in the shadow of the pines, all that was mortal of the murdered city treasurer was laid to rest. The services at the grave were short and simple.”

The New Castle News of Wednesday, January 11, 1899, also reported, “The police are wholly at sea regarding the crime and as far as can be learned they are entirely without clue regarding the perpetrators or perpetrator of the crime. It is now certain that the murder occurred about 10:15 o’clock Saturday night, although the crime was not discovered until after midnight. It is not known how much money was taken, but it is thought the robbers got $500. The police are of the opinion that the crime was committed by some one who was well acquainted with the office and with whom the dead man was also well acquainted.”

The New Castle News of January 15, 1899, reported, “The work of the coroner’s Jury is now ended and whatever further light is thrown on the mystery must come from other sources. Detective S. B. Marshall, Chief of Police McClain and Postmaster John B. Brown, together with all the police and constables of the city have not relaxed their vigilance in the east, but are keeping a sharp lookout for anything that may lead to a possible clue. As has been stated on several occasions the assassin left no clue of any value in the treasurer’s office and whatever is developed must now come from other sources. Those who believe in the old saying that “Murder will out,” maintain that the murderer cannot keep his secret but will yet betray himself by some act, word or deed. There are others who are not so confident that the assassin will give himself away and in support of their views point to the long list of murders committed over the country in past years and which are yet shrouded in the deepest mystery.”

In the coming weeks several suspects were identified, including a career criminal named Charles Blanco. Police officials arrested Blanco in Franklin in Venango County and transported him to New Castle for questioning. He was cleared in late January as it was learned he was in Ellwood City on the night of the murder. He was sent back to Franklin and charged with various other crimes involving theft. The investigation soon grew quiet and in March 1899 the Perkins Detective Agency of Pittsburgh was called in to assist the local police.

To jumpstart the investigation Blevins’ remains were secretly exhumed on the early morning of April 7, 1899, by a team that included Dr. James K. Pollock, Dr. Edmund A. Donnan, and Dr. Jesse G. Moore. The head was removed for a detailed examination and the body was reinterred. The task was carried out quietly before most people were even awake.

Months later, In July 1899, the public was shocked as authorities finally released details of the exhumation and examination. The New Castle News of July 19, 1899, reported it this way, “The coffin was opened at 5 o’clock, and 10 minutes later, the physicians were ready for its re-interment. The head was brought to Donnan’s office in a sealed box. It was in an excellent state of preservation. The same evening, the physicians went to work. They first examined the head as it was. A description was made of each wound. There were 18 in all. They were found to range from half an inch to three inches in length. There were none on top of the head. They started at the left temple and ran clear around the crown to the other side. Those on the left side were made at an angle of about 15 degrees. None of these wounds had disturbed the pericardium. The skull had not been fractured here. The wound in the back of the head, which was “popularly” supposed to have been the cause of death, was merely a flesh wound. The wound which did cause death was on the right side of the face. On the surface it was a mere contusion, and at the time of the previous examination had been so regarded. The victim’s face was very much discolored, and it was supposed to be due to these bruises. Underneath the contusion, however, was a fracture. The sides of the skull were pressed together unnaturally. There was a fracture on the other side. As Mr. Blevins lay on the floor, his left side under him, the death blow was directed downward, and with great force. A man’s heel is the only thing which would have inflicted such an injury. A downward blow from a club or bludgeon would not have caused a fracture on both sides and broken both the nose and jawbone. The former was broken loose at the extreme upper part and the murderer wore either rubber boots or rubber overshoes. Had he struck with his unprotected shoe heel there would have been marks on the outside to show it.”

The police had previously received several anonymous notes from someone alleging to have information about the murder. The notes, apparently of little value to the investigation, were never made public. Finally, on Monday, April 15, 1901, in a confusing twist, Blevins’ close friend Perry Douds was charged in connection with the letters.

The New Castle News of Wednesday, April 17, 1901, reported, “The arrest of Perry Douds, who was charged with obstructing justice in the Blevins case, created a big sensation in the city on Monday and nothing else could be heard on the streets the rest of the day. The information as made by J. L. McFate, stated that some letters, supposed to have been written by M. Douds, had been found and were never made public. These are in the hands of the people who are making their investigation and the contents are being kept secret. The News had an extra edition on the streets at 2 o’clock and the papers were fairly snatched out of the newboys hands by the eager public. Nearly 4,000 copies of The News were sold by 4 o’clock and by that time the sensation had spread all over the country. Telephones and telegraph wires were kept busy all afternoon by people from a distance who had heard of the affair and were anxious to get the full particulars… Mr. Douds is deeply humiliated by the charges made against him and says the fact that he is charged with doing this thing almost breaks his heart.”

Douds went on trial in June 1901 and after proceedings of two weeks he was acquitted of all charges. It was a rather embarrassing affair and Douds was obviously not responsible for the letters. The investigation dragged on and officials from the famous Pinkerton Detective Agency were called in to assist for a time. In early 1902 the City Council and County Commissioners were close to an agreement to raise the reward to a total of $10,000, but this apparently never came to fruition.

In the summer of 1903 a career criminal named James McPhillamy was named as a potential suspect, but was quickly cleared as it was learned he was in jail in Pittsburgh back in early 1899. In January 1904 a prisoner in Westmoreland County named Charles E. Kruger, condemned to death for killing a local constable, confessed to killing Blevins. His confession was discounted as a simple attempt to delay his execution. He was hanged to death in Greensburg on February 11, 1904.

In March 1908, Ruth Blevins, who apparently never rebounded from her husband’s tragic death, suffered a nervous breakdown and was sent to a sanitarium. She passed away soon after and was buried next to her husband in Greenwood Cemetery.

In June 1908 a former New Castle resident and career criminal named Addison Ruth (aka Frank Barnes), incarcerated in the Venango County Jail in Franklin, began to receive publicity because he seemed he knew specific details about the case. For several years he had been saying he knew who killed Blevins. He said the killer was notorious criminal Dan Wilder and two accomplices named Gene Parker and William Farrell. After the trio robbed and killed Blevins they split up, with Wilder and Parker heading north together. Wilder then killed Parker and buried him in Elk County. Bones were later found at the location which seemed to lend credence to at least that part of the story.

New Castle attorney C. Henry Akens was tasked by authorities to go to Franklin and question Ruth. Akens investigated the story, but in the end nothing came of it. Again, it was probably a case of an inmate trying to lessen his sentence. Ruth and Wilder, both in jail for various offenses, had also committed a robbery together at Pithole in Venango County. In May 1909, when they were sentenced for Pithole robbery, Wilder received a six-year prison sentence, while Ruth (for his cooperation) only served another year at the jailhouse in Franklin.

Meanwhile, on the financial front, investigations and audits revealed numerous irregularities in the business practices of Blevins, who had been City Treasurer for about thirteen years. It appears in addition to the stolen $500 in cash, the assailants also made off with seven city bonds from 1886 worth a total of $3,500. Blevins had been holding the bonds for the owner – a recently deceased wealthy farmer in Petersburg, Ohio, named Hugh Martin. Another man from Mount Jackson, identified only as Hogg, was now claiming ownership. Regardless of who owned the stolen bonds it was quite unusual for a city official to be holding bonds for a private party.

In late 1898 the City Council had ordered an independent audit of the City Treasury funds. This was to be the first audit in over ten years and the murder occurred before it commenced. Two in-depth bookkeeping audits revealed different results. But the bottom line was that anywhere from $26,000 to $50,000 (or possibly even as much as $75,000) was missing dating back to 1893. Just what happened to this money, most from the school board budget, was uncertain and this resulted in a major scandal. The school board was owed as much as $27,000 in collected taxes that never made it to its budget. The school board later sued the Blevins estate to recover the money, but there was no money to collect. It was not until November 1923 that the school board officially dropped its claim against Blevins estate.

Blevins, although a unskilled and informal bookkeeper, was known as an honest and frugal man and few people thought he might have been embezzling money. However, many questions remain about the discrepancies. Did Blevins misappropriate the missing funds? Could Blevins have secretly loaned the city money to a friend and was then killed when he attempted to recover it? Could Blevins have been murdered as part of a cover-up or blackmail scheme? Was a corrupt city official behind the murder to silence him?

Various prominent local businessmen had acted as bondsmen for the City Treasury funds. In March 1900 the City of New Castle went to court to attempt to force the bondsmen to pay for the missing funds. This resulted in often bitter and prolonged legal battles that stretched over two decades. It wasn’t until the early 1920’s that the various legal cases were all settled.

Another case involved the First National Bank of Lawrence County suing the City of New Castle to recover a loan of $5,431.49 given to City Treasurer Blevins in September 1898. Several other banks were also seeking repayment of much smaller loans given to Blevins. These cases all went to court and stretched out over the next decade. The City of New Castle claimed although Blevins borrowed the money (and the money may have been used for city purposes), he did so without the consent of the City Council. A judge in Butler eventually ruled in favor of the City of New Castle and determined that Blevins had no legal authority to vouch for loans in the name of the city. The case was appealed all the way to the Pennsylvania State Supreme Court, which reaffirmed the decision in February 1913.

Meanwhile, the murder investigation grew cold but was never forgotten. The New Castle News of Wednesday, January 8, 1936, reminded people, “It was 37 years ago last night since City Treasurer John Blevins was murdered. This greatest mystery crime in the annals of Lawrence county is still fresh in the minds of older persons, but a new generation has grown up, many of whom have learned but vaguely of the crime that shocked the community on that memorable Saturday night, January 7, 1899.”

The News Castle News of January 7, 1999, reported on the 100th anniversary of the crime with, “Despite theories on motive and identity of the killer or killers, the murder of the 70-year-old treasurer has never been solved. There is no statute of limitations on homicides, but Lawrence County District Attorney Matthew T. Mangino said, “From a practical standpoint, there’d be little likelihood you could find any evidence to proceed.” The Blevins case, which will be 117 years old in January 2016, remains New Castle’s most notorious and longest-running unsolved murder.

|

On the late afternoon of Sunday, July 12, 1908, a group of people were playing cards in a house at #118 Valentine Street in New Castle, Pennsylvania. The residence was the rented home of forty-nine-year-old Italian immigrant named Fred Rosena (Ferdinand Rosrno). He lived there with his Italian wife Frances, his three small children, and two of his sisters. Valentine Street is no longer on modern-day maps, but it was roughly west of Produce Street along South Croton Avenue.

Rosena, who was born in Italy in 1860, had come to this country as a teenager and settled in New Castle in 1883. He was married in about 1902 and started a family. He was well-known around the Italian community, as a con man and gambler. He had occasionally been employed as an interpreter with the Lawrence County Court House. He was part of a celebrated lawsuit in late 1904 in which he sued the county commissioners for $50 he said they owed while employed as an interpreter. The court ruled against him.

He was known to be violent and had several run-ins with the law dating back a decade. One of the worst incidents was took place in December 1900 when he had been involved in a vicious knife fight with a man at the Union Depot on Pittsburg Street (East Washington Street). Both men were injured, but the other man – who was stabbed in the back – was hospitalized for some time. Rosena was charged with assault and attempted murder but was eventually cleared. In more recent years he had also been cited for threatening or assaulting his wife on numerous occasions.

Back to the evening in question, July 12, 1908, a dispute of some sort ended the card game and several neighbors departed. Fred Rosena and his wife and her cousins John Chocco and Philip Chocco remained. John Chocco had apparently come up from Pittsburgh about two weeks prior to stay with his cousin (Mrs. Rosena). A physical altercation of some sort ensued between Rosena and John Chocco. Rosena rushed into a back room and reappeared with a loaded .38-caliber Winchester rifle.

NOTE: Various reports refer to John Chocco as the “brother-in-law” of Fred Rosena. After in-depth research I don’t believe this to be true. Chocco was a cousin of Mrs. Frances Rosena – and not her brother.

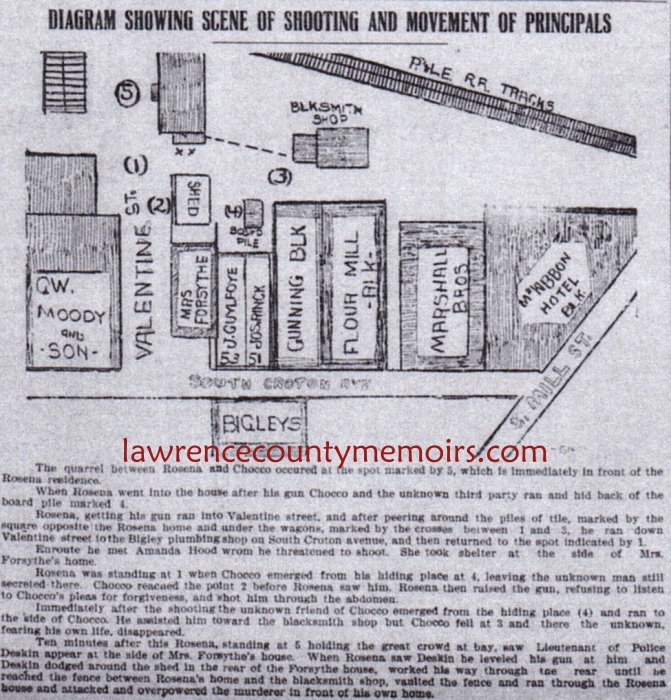

Meanwhile, John Chocco, also known to have a violent past, and his brother Phillip fled the house and hid out nearby. Rosena, brandishing the rifle, went out onto the front porch and looked around. He was angered could not find John Chocco and then walked up to Croton Avenue looking for him. He then returned towards the house, threatening several people along the way. A neighbor named Amanda Hood said he attempted to shoot at her, but the gun misfired. Once he returned to the house John Chocco suddenly appeared from hiding with his arms raised. Chocco initially attempted to reason with Rosena and according to witnesses he then begged for his own life.

The New Castle News of Monday, July 13, 1908, reported on the subsequent events with this, “As Chocco approached Rosena the latter muttered something and raised his rifle to his shoulder and snapped it. The first trial failed for the rifle appeared to be out of working order. Rosena, however, seemed to know what was wrong, for he took the gun and shook it violently and pounded the magazine on his hand. When it was all right again he deliberately raised it to his shoulder and stepping forward a few feet – for Chocco, seeing Rosena was determined, had backed back – fired point blank at his victim. Chocco staggered, placed his hand on his side and tottered” continued (witness John) Guylfoye. “Then the third man came from behind the board pile and ran to Chocco’s side. He assisted Chocco towards Vogan’s blacksmith shop in the rear of the Rosena house and there the wounded man played out and sank to the ground exhausted. Rosena had been watching the two men and when the third man saw Rosena following them he deserted Chocco and disappeared, and has not since been seen.” The article went on to report, “As soon as Chocco was left by his friend several persons started towards the wounded man. Rosena leveled his rifle at these and ordered them to get out of sight, which they readily did.”

Rosena chased after a group of bystanders and threatened them as they scattered. He then returned to his porch and stood looking out as a curious crowd began to gather in front of the porch. Chocco, shot in the abdomen, lay dying just fifty feet away. Rosena, with his four-year-old daughter Rosie hanging on his leg, murmured at the crowd but remained calm. Several police officers soon arrived on scene and surveyed the situation. James “Jim” Deskin, the Irish-born Lieutenant of Police for the New Castle Police Department, pushed his way through the crowd and was immediately threatened by Rosena. Deskin had arrested Rosena before and was well aware of his temper.

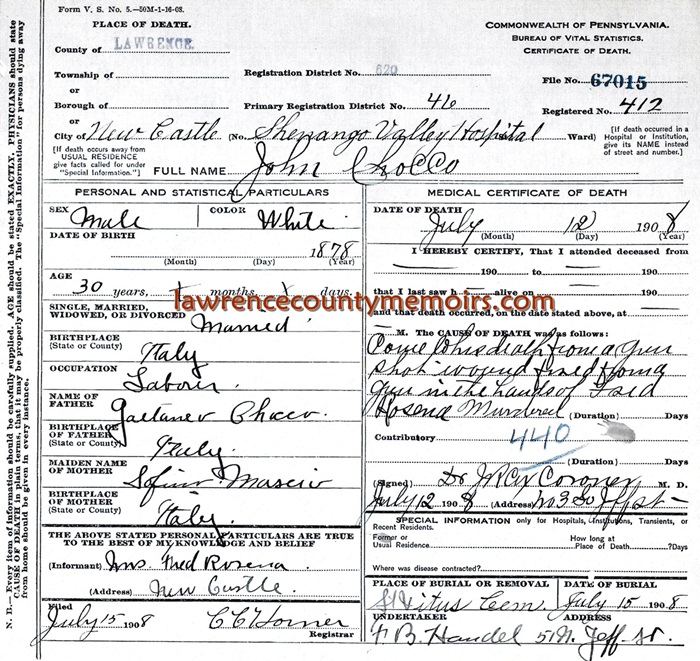

Deskin backed away and then made his way around to the rear of the Rosena house. He entered the rear door, rushed through the house, and exited out the front door. Rosena saw the approaching officer at the last second, but it was too late. Deskin disarmed him with one hand and landed an uppercut with the other. A stunned Rosena fell off the porch and Deskin was quickly on top of him. Rosena was put in handcuffs and led back into the house. Rosena reportedly told the police he was glad he had killed his victim. Chocco was rushed to the Shenango Valley Hospital and underwent surgery for four hours. He died of his gunshot wound later that evening. Before surgery he reportedly told police that Rosena shot him over a dispute over money. The crowd was cleared and Rosena was then led to the police station in the basement of the City Hall building. On Wednesday, July 15, Chocco was laid to rest in St. Vitus Cemetery in Shenango Township.

Police were initially believed the fight was over money, but another possible motive was soon developed. The New Castle News of Monday, July 13, 1908, had this to report, “It seems that Rosena’s abuse of his wife has had much to do with it. Rosena’s treatment of the woman has been almost inhuman. Several bald spots on her head show where he, in his fury, has pulled her hair out by the roots. Great patches the size of dollars testify to his barbarous treatment of her. Neighbors and police records also tell of the outrageous treatment to which she has been subjected. Amanda Hood has written several letters to the district attorney for Mrs. Rosena asking if there is not some relief for her – some protection from her husband. “That is why Rosena was so willing to kill me this afternoon when he was out killing,” said Mrs. Hood by way of explaining Rosena’s motive for pointing and snapping the gun at her. Two weeks ago John Chocco left his wife at Pittsburg and came to New Castle to make his home with… Mrs. Rosena. He explained that his wife had taken up with another man, but Rosena did not believe this. He believed that Chocco was there at the instance of Mrs. Rosena or some other who wished to interfere with Rosena’s home affairs – with his privilege of beating his wife whenever he desired. It is believed to have been this suspicion of Chocco that led to the shooting Sunday afternoon.”

On the afternoon of Monday, July 13, Rosena was taken upstairs from his cell in the City Hall building and provided with a hearing before Mayor Harry J. Lusk. Lusk ordered him held without bail pending a court date the coming September. Rosena was soon taken to the Lawrence County Jail. Among his fellow inmates was the infamous Black Hand leader Rocco Racco, who was later executed for his part in killing game warden Seeley Houk back in March 1906.

Rosena was initially defended by C. Henry Akens, but he withdrew later that fall. Soon after this the court appointed attorneys William J. Moffatt and Wylie McCaslin to defend Rosena. On Tuesday, September 8, 1908, Rosena was formally indicted for the murder of John Chocco. His new legal team immediately asked for a three-month delay in the trial and Judge William E. Porter granted it. Rosena would remained locked in the county jail until his trial began.

Rosena was called upon to testify in the trial of Rocco Racco in mid-September 1908. The New Castle News of Wednesday, September 16, 1908, reported, “A sensational feature of the trial Wednesday morning was the testimony of Fred Rosena, who is in jail for the murder of his brother-in-law. Rosena contradicted the testimony which he had given before Alderman Green. He said there that Racco had threatened Houk’s life but in court claimed Racco said he would kill the man who killed his dog. When asked why he changed his story he said that Racco had threatened to kill him in the county jail for testifying as he had done before the alderman.” Racco was soon convicted and then sentenced to death.

In the middle of November reports surfaced that Rosena, who was very sick with the flu, had died in jail. The jail officials, led by Lawrence County Sheriff John W. Waddington, had to ensure folks this was not the case and Rosena would be fit to stand trial.

Jury selection began in early December 1908 and was a tough task as everyone seemed to have a strong opinion on the case. The trial began on Tuesday, December 15, 1908, in the courtroom of Judge Porter. Prosecuting the case was District Attorney Charles H. Young, assisted by attorney Roy M. Jameson. Rosena entered a plea of not guilty. He claimed that he was afraid of the Black Hand Society, the Italian criminal organization, and had purchased the weapon used in the murder for the protection of his family. During the trial Rosena’s wife testified on his behalf. A key witness to the murder, Phillip Chocco, had fled immediately after the murder and was never located.

Rosena testified that he had killed John Chocco in self-defense after the two had gotten into an argument over money matters. The New Castle News of Thursday, December 17, 1908, reported on Rosena’s testimony with, “Placed on the witness stand in his own defense, Wednesday afternoon, Fred Rosena, charged with the murder of John Chocco, gave his version of the trouble at the Rosena home of July 8… He said that following a card game at the Rosena home on the fateful Sunday afternoon, he had become involved in a dispute with Coccho and that Coccho had grabbed him by the throat and threw him down. Coccho, he said, then picked up a huge butcher knife and was about to out his throat when Mrs. Rosena dragged him off. Coccho said he would kill Fred until he was six feet under the ground. Coccho left the house but came back again and renewed the quarrel. It was then that Rosena secured his gun, Rosena claimed that Coccho was standing between him and his home when he fired and that he did so to protect his home. Mrs. Rosena, who was on the witness stand all afternoon Thursday, also testified that Coccho had assaulted her husband and bad dragged him to the kitchen. Coccho was in the act of drawing a butcher knife on Rosena when she interfered. Mrs. Rosena claimed that Coccho had pointed the knife at her and had threatened that he would kill both her and Fred before he left the house.”

Mrs. Rosena testified, “She had known John Chocco on Italy. In fact he had wanted to marry her. She said he was a bad man and had been arrested 12 times in Italy and had tried to stab his mother. She said John Chocco had come to this city from Pittsburgh to avoid arrest.” She was then cross examined, “Did not John Chocco come here during the month of June in response to a letter written by you? asked District Attorney Young. “Yes, we wrote back and forth. I gave the letters to my husband to mail.” “Did you not write to Cocho (sic) and tell him to come here because your husband was abusing you?” Objection was raised to the question. Objection sustained. Mrs. Rosena then explained that Coccho had written her saying he wanted to come here and she had answered if you want to come then come.”

The trial lasted three days and ended on Thursday, December 17, 1908. The jury deliberated all night and reached a verdict before the court reconvened at 9:00am the next morning. The New Castle News of Friday, December 18, 1908, reported, “Rosena, who stood with uplifted hand, while the jurors each answered “Guilty of murder in the first degree,” was visibly affected although he stood up well, as his doom dropped from the lips of the twelve men. Mrs. Rosena, who sat beside her husband, also bore up bravely, and there was no “scene” in the court room. Immediately after the verdict had been pronounced Rosena was led back to the county jail. He had nothing to say.”

An appeal was soon filed by Rosena’s attorneys and a hearing for a new trial was held before Judge Porter on Friday, March 5, 1909. Porter considered the motion and ruled against it, while announcing his decision on Wednesday, June 23, 1909. That same day the New Castle News reported on how Rosena took the news, “He grew very pale when the decision was announced. As Sheriff Waddington led him back to jail his eyes filled with tears and by the time his cell was reached he sank on the hard floor, wailing and sobbing like a child.” The Reverend Nicholas DeMita, his spiritual adviser and the pastor of St. Vitus Catholic Church, would provide him with comfort in the coming months.

Two days later Rosena was back in the courtroom to hear his sentence. The New Castle News reported, “The sentence of the court is that you, Fred Rosena, suffer death by hanging and that you be detained in the county jail until such time as the governor may fix for your execution, and may God may mercy on your soul. In a deathlike stillness that pervaded the court room Friday morning Judge Porter thus pronounced sentence on the murderer of John Coccho. Rosena, pale trembling, his eyes glancing furtively about the room, stood before the bar of justice. “Thank you” he said, as the court ceased speaking, and turning, was led from the court room by Sheriff Waddington.”

At that time executions in Pennsylvania were handled by the local counties, and in this case Lawrence County Sheriff John W. Waddington would be responsible for the execution of Rosena. It wasn’t until 1913 that the state took over responsibility for all state-wide executions, and mandated electrocution as the preferred method of execution.

The New Castle News of Friday, October 22, 1909, reported, “Governor (Edwin) Stuart has fixed Thursday, December 2, as the date for the execution of Fred Rosena, convicted of the murder of John Coccho. This will bring the execution within the term of office of Sheriff Waddington. If the Rocco Racco execution takes place as scheduled (on October 26) and Rosena is granted no respite, it will make the fourth hanging for Sheriff Waddington since he assumed the duties of his office. This is remarkable as in the history of the county there was only one execution, that of Frank Jongrass, before Sheriff Waddington assumed office. Waddington has already hanged Rosario Serge and Charles Quimby. The crime for which Rosena is to stretch hemp was probably one of the most cold-blooded murders that has ever been committed.”

In late November an application was made to the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons to have Rosena’s sentence of death commuted to one of life imprisonment. The application was denied. The Reverend Nicholas DeMita, a leading voice in the local Italian community, sent off a last day telegram asking Governor Stuart for leniency. The governor replied with, “After careful consideration of the request contained in your telegram for a respite in the case of Fred Rosena, in view of the fact that the board of pardons has refused application for commutation of sentence, I have concluded not to interfere with the judgment of the courts. Edwin S. Stuart.”

The New Castle News of December 2, 1909, had this to say about the sad evening before the execution, “Rosena last night was shaved and after alighting from the chair In which he had been propped for the barber, he danced around the sheriff and had playfully put up his fists and had said he wanted to fight. He was In the best of spirits, apparently, from the sheriff he went over in front of his little son and did a clog and low monkey dance that threw the youngster in a fit of laughter. Mrs. Rosena standing aside with tearstained eyes viewed all of this with a faint smile. Following this Rosena and his little family were left alone for some time and when It came time for them to part for all time, Mrs. Rosena utterly broke down. She was in a worse state of collapse than her husband. Repeatedly he sought to cheer her but she would not or could not listen. Finally the guards gently drew her away and as they did so her screams could be heard to the streets outside of the jail. In Italian she shrieked repeatedly, “O, my God!” “O, my God!” Once she broke loose from the guards and ran back and threw herself on her husband and there a flood of tears relieved her of her hysteria for a moment. At her skirts clung her children and at last the combined efforts of all the guards were required to move the heart-broken woman who continued her agonizing screaming far out of the jail and down Pittsburg Street.”

On the morning of Thursday, December 2, 1909, Rosena was led to the gallows set up in the courtyard of the Lawrence County Jail. The New Castle News reported on the execution with, “Fred Rosena was fighting mad when he went to his death on the scaffold this morning. There was nothing of the coward about him. He did not think so much of his impending death as he did of making “a speech that would make them smart.’ He made the speech all right and he spoke right out in meeting, with a voice firm and strong; and from a mind that appeared to be clear, but the speech was not so bitter as was expected from those who had been with the man during the last hour of his life. He said: “Gentlemen, I am much obliged for the chance to talk. I am a citizen of the United States. I belong to Uncle Sam. I am a free man. I am going to my death honestly and because I defended my family. I got no justice in my trial. That was because some of them were against me. They do not want honest men in this country. I’m done. Goodbye.”

At about 10:17am, after being hooded, Sheriff Waddington pulled the lever and sent Rosena to his death. He was declared dead at 10:30am by Dr. Elmer P. Norris. The remains, prepared by the Lutton Undertaking Company, were taken to the Rosena home on Valentine Street for a wake. The next morning a small service was held at St. Vitus Catholic Church and afterwards the remains were interred in St. Vitus Cemetery. It was a sad ending to a senseless crime.

At some point Frances Rosena was remarried to John B. Matura, an Italian immigrant who operated a grocery store on South Jefferson Street. Matura was no stranger to trouble, as he was cited for gambling and other criminal offenses on several occasions. In the summer of 1919 fifteen-year-old Rose Rosena, the oldest daughter of the late Fred Rosena, fled the house and moved in with an aunt named Mary Stephano. Rose claimed that her mother was beating her. What followed was a nasty legal battle that continued on for several years. In those days children were not generally considered adults until they reached the age of twenty-one. The case appears to have been settled in the summer of 1923 and Rose, then aged nineteen, was allowed to determine her own living arrangements. It’s presumed that Frances (Rosena) Matura, who became a naturalized citizen in 1913, lived out her days in New Castle.

|

A drawing of the murder scene along Valentine Street. (1908) |

The death certificate of John Chocco, which oddly enough lists the cause of death as “from a gun shot wound fired from a gun in the hands of Fred Rosena Murdered.” I don’t think that would fly today… not without a trial and all to determine official guilt. (1908) Full Size |

Text Coming Soon!

|

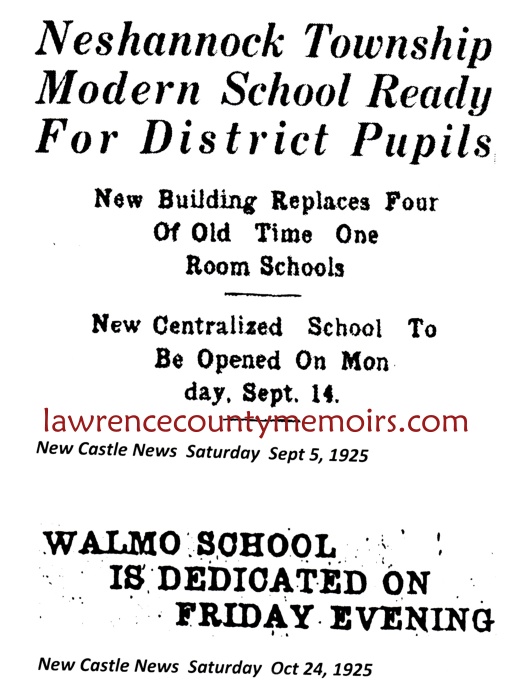

The four-room Neshannock Public School, usually called the Walmo School, was opened on East Maitland Lane in September 1923. It handled students in grades 1-8. It was dedicated during a ceremony on Friday, October 23, 1923. Due to severe overcrowding in the township a four-room addition was completed in August 1949. The building was re-designated as the Walmo Elementary School in 1955. It remained in service for over five decades until it was closed in June 1977. (c1925) Full Size |

I believe this photo depicts a first grade class at Walmo Elementary School in 1966. The teacher is Mrs. Mary Bratchie Patton. (1966) (Photo posted on Facebook page of “Walmo Elementary School”) |

|

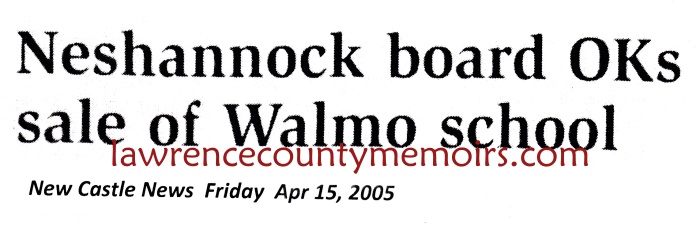

After the Walmo School closed in 1977 it subsequently served as the home for several specialty schools and organizations in the coming years. In 2005 the township sold the building and it became the new home of the Cray Education Center, an alternative school for troubled teenagers. (Sep 2013) Full Size |

(Sep 2013) |  (Sep 2013) |

(Sep 2013) |  (Sep 2013) |

The former Walmo School on East Maitland Lane (seen at bottom of photo) is now home to the Cray Education Center. (c2012) Full Size |

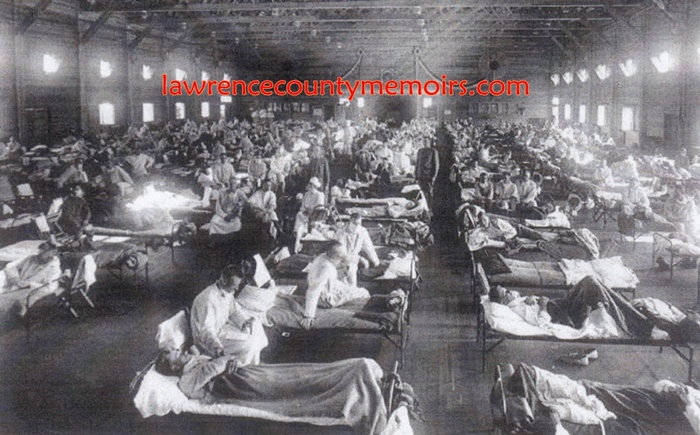

On Monday, March 11, 1918, in the midst of the Great War (World War I), a U.S. Army private named Albert M. Gitchell checked himself into the infirmary at Fort Riley, Kansas, complaining of a sore throat, headache, and fever. By the end of the day over a hundred of his fellow soldiers were also ill with identical symptoms. The men were all suffering from a new strain of the Influenza A virus known as H1N1, later known popularly known as “swine flu” due to its prevalence among pigs. The outbreak at Fort Riley quickly spread and when it was finally under control by the end of April 1918 a reported 1,127 soldiers were sick and 46 of them (but not Gitchell) had died.

Fort Riley was one of the initial hotspots of this extremely contagious strain of influenza, but its actual location of origin is still debated today. Other military installations in the United States experienced similar outbreaks, and before too long infected troops being sent “Over There” brought the sickness to the front lines of wartime France. The flu quickly afflicted all of the war-torn countries of Europe, and then began to spread throughout the entire world.

Wartime censorship actually hid the news from the general public for a few months. It wasn’t until late May 1918 when the newspapers in the neutral country of Spain, where King Alfonso XIII was gravely ill with the flu, reported on the pandemic and made it an international story. It was these reports that led to the outbreak, although it did not originate in Spain, being dubbed as the “Spanish Flu.” It was also known by the French phrase “La Grippe” (The Grip).

The outbreak took some time to spread, but was generally over by the late summer of 1918. At this point the extremely contagious Spanish Flu was a serious medical concern, but was not particularly deadly. However, like most flu outbreaks, it would strike in several waves and the next wave would afflict the world’s populace like never before or since.

In mid-September 1918 the city of Boston, Massachusetts, (and a few other locations in France and Africa) began to suffer from a new wave of the Spanish Flu. The influenza had obviously mutated and this second wave was marked by an unusual feature: An extremely high mortality rate, especially among healthy young adults aged 15-25. Almost 4,000 Bostonians died from the respiratory illness in the next month, and before too long the entire country was under siege from the deadly influenza bug.

In early October 1918 the first reported cases of this second wave of Spanish Flu began to hit New Castle, Pennsylvania. Mayor Archibald D. Newell, the City Council, City Health Officer Dr. William L. Steen, City Physician Dr. James K. Pollock, and County Coroner Elmer P. Norris began meeting to come up with a plan of attack to fight the local epidemic. Dr. Steen, a University of Pittsburgh graduate who served as the City Health Officer from 1915-1943, led the effort until he was departed in mid-November 1918 to serve with the U.S. Army. The seventy-three-year-old Dr. Pollock, a well-known and prominent local citizen, became acting Health Officer in Steen’s absence.

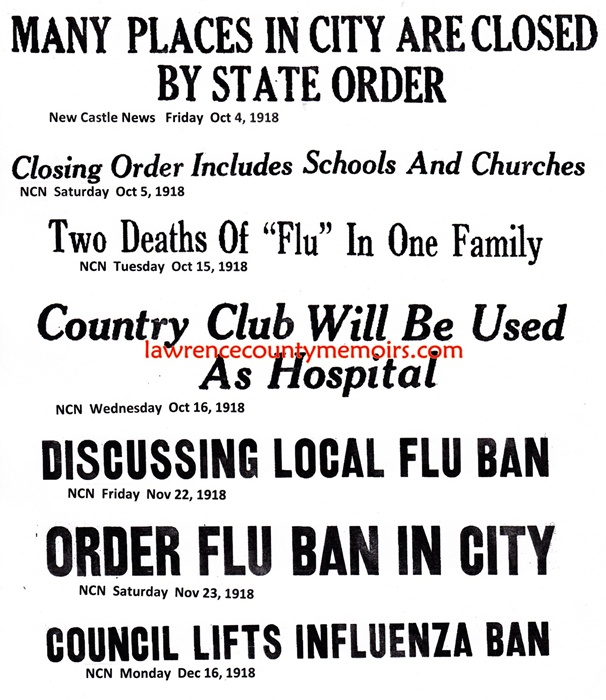

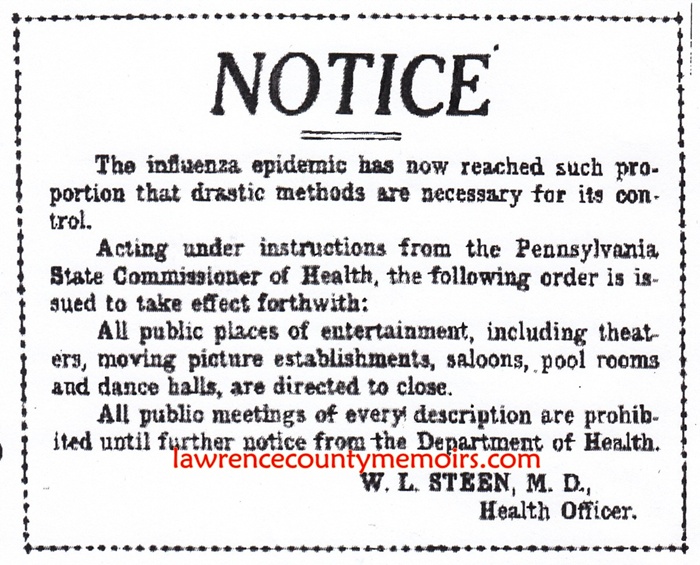

An unprecedented “Flu Ban” went into effect on Friday, October 4, as all schools, churches, theaters, saloons, wholesale liquor stores, billiard rooms, dance halls, fraternal lodges, and other public meeting places were closed until further notice. Sick persons were ordered quarantined in a separate room in each afflicted house. An “anti-spitting ordinance,” backed by a $1 fine and a possible short jail term, was enacted to authorize the police to arrest anyone caught spitting in public. Other measures included limited attendance and a quick pace at weddings and funerals, a discouraged use of public transportation, staggered employee hours at large factories, and the mandatory reporting of all cases of illness to the City Health Officer. Retail businesses were allowed to remain open, but people were warned to exercise caution when shopping.

Sunday, October 6, 1918, was reported to be one of the quietest days in the history of New Castle. That day was already a “Gasless Sunday,” a wartime initiative to save gas and support the military effort in Europe. Now with all city churches ordered closed for the first time ever the downtown area was literally deserted. Most residents simply sheltered in their homes hoping to avoid the Spanish Flu.

The most serious patients were admitted to the Shenango Valley Hospital on North Beaver Street, which was quickly filled to capacity. On Wednesday, October 16, the City Council decided to set up an emergency hospital at the New Castle Country Club (or Field Club) along Vine Street in the Croton area of the city. At this time there were a reported 242 cases of the Spanish Flu in the city and the American Red Cross joined the fight. Upon approval of Dr. Steen, the City Health Officer, any physician could admit a patient to the emergency hospital at a cost of $1.50 a day. The Red Cross, augmented by hundreds of local volunteers, ran the hospital and other outreach programs.

By the end of October there were a reported 864 cases of influenza in New Castle. Most of those were concentrated on the East Side and South Side sections of the city, with a few isolated cases in Mahoningtown (mostly with transient railroad men) and on the North Hill. The West Side was fortunate and remained almost free of the Spanish Flu. Afflicted persons were quickly overwhelmed with chills, fatigue, headache, high fever, and delirium. Many of the afflicted coughed up blood and developed cyanosis, a bluish discoloration of the skin. A small percentage died within a day or two of feeling ill and those that survived often developed aggressive forms of pneumonia or tuberculosis.

Ellwood City also faced a similar crisis and had a reported 555 cases of Spanish Flu by October 28. An emergency hospital was established at the old Polish Club building at Crescent Avenue and Tenth Street. In late November the influenza began spreading into the neighboring areas of North Sewickley Township, Frisco, and Wurtemburg. With New Castle and Ellwood City locked in a struggle it was almost impossible to assist the outlying communities throughout Lawrence County. Wampum (and the neighboring locales of Clinton and Coverdale) was probably the worst off of all the smaller villages in the county. The Crescent Portland Cement Company, assisted by the Red Cross and local volunteers, took the lead in battling the outbreak in that area. Others areas facing a substantial number of influenza cases included West Pittsburg, Bessemer, Hillsville, New Wilmington, and Volant.

The medical community was ill equipped to meet the threat and treatments did almost nothing to help. Several new or existing vaccines were being tested, but without a real understanding of the causes of the flu they were ineffective. Doctors were relying on techniques learned during the large scale influenza outbreak back in 1889-90. It wasn’t until the 1930’s that researchers, learning that influenza was caused by a virus vice bacterium, began making strides to develop a successful influenza vaccine. The situation in 1918 was made worse by the fact that many of the nation’s qualified medical personnel were off serving in the military. And they would be needed because of the 117,000 total deaths suffered by the U.S. military during World War I, about 43,000 of those succumbed due to complications from the Spanish Flu.

What did work was a host of preventive health measures such as advocating the wearing of gauze masks, quarantining sick patients, and closing public meeting places seemed to stem the tide of the outbreak. Many people also devised their own home-grown remedies, which often included the use of onions. An article in the New Castle News of October 20, 1918, advised that the Reverend Wilbur G. Volivia, a famous Zion evangelist, advised people to eat onions because “No germs like onions” and “besides if you eat onions people will stay away from you and that is important in checking the influenza epidemic.” Alcohol was also believed to help, but with saloons and wholesale liquor stores closed it was hard to come by.

On Monday, November 4, there were a reported 1,019 cases of influenza in New Castle, though the outbreak was largely under control. A high-profile local casualty took place on the evening of Thursday, November 7, when forty-eight-year-old County Coroner Elmer P. Norris, who survived a bout with the influenza, died at his residence on North Jefferson Street due to complications from flu-related pneumonia. A few days later, on Sunday, November 10, the flu ban in New Castle was lifted and all schools, churches, theaters, and other public meeting places were reopened. This would prove to be a costly mistake.

The next day the headline of the New Castle News read, “IMPOSSIBLE FOR HUNS TO RESUME WARFARE,” while a sub-headline announced, “BIG WORLD WAR COMES TO AN END AT 6 A.M.” The Armistice officially ended the hostilities in Europe and local citizens, already relieved by the end of the flu ban, were excited to read all about it. Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, proved to be a complete disaster. As expected local citizens poured into the streets to celebrate, mingling with strangers, hugging and kissing each other, and sharing cigarettes.

There was a brief lull, but after a week or so the Spanish Flu was back in full force. On Friday, November 22, city officials met for hours to decide what action to take. They enacted a new flu ban, this time with more stringent measures, to commence at 6:00 p.m. the following day. At noon on November 23 it was reported that ninety-five new cases had been reported in the last twenty-four hours, bringing the total since early October up to 1,956 cases.

The new ban once again closed schools, churches, and all other public meeting places, but also placed severe restrictions on street cars. Street cars officials were ordered to carry only a limited number of patrons at one time, keep the windows open at most times, and to clean the interiors of the cars on a regular basis. Notices were placed on the front doors of homes where sick people were quarantined advising, “Spanish Influenza, stay out, by order of the Board of Health.” Citizens were also warned about the dangers of kissing, urged to use their own dedicated eating utensils, and reminded to keep their fingers out of their mouths when in public.

Prominent civic leaders meet with city officials on Wednesday, December 4, 1918, to discuss the situation. Businessman George Greer, who founded the tin mill industry in New Castle, was selected to head up a committee to explore ways the public could assist the official effort. O.J.H. Hartsuff, an executive with the Carnegie Steel Company, served as chairman of a Red Cross fundraising drive from December 16-24.

The Red Cross Emergency Hospital at the Country Club, suffering from a lack of heating and also proper sanitary facilities, was moved to the larger Knights of Columbus home on North Jefferson Street on the evening of December 4. The Red Cross soon set up a command center in the Masonic Lodge on North Street, and later moved to the Safe Deposit and Trust Company building on North Mercer Street in March 1919.

The influenza outbreak was soon brought under control and the second flu ban was lifted on Monday, December 16. Churches and other public meeting places were authorized to reopen, but public and parochial schools were to remain closed for another few days. Churches were reopened just in time for holiday services.

The New Castle News of Thursday, January 9, 1919, reported, “The influenza epidemic is believed to be a thing of the past if the health reports may be taken as the basis of such an opinion.” The same article also pointed out that no new cases had been reported in the last three days. A third wave of the Spanish Flu struck in the early months of 1919 and periodic cases were reported in New Castle until the early summer. The Spanish Flu continued to rage in other regions of the world, but basically ran its course by the fall of 1919.The United States suffered 675,000 total deaths from the Spanish Flu and Pennsylvania was hit particularly hard. During October 1918 the state suffered a reported 28,505 deaths from the flu, 8,433 from pneumonia, and 1,379 from tuberculosis. A large portion of those deaths occurred in Philadelphia, where officials were slow to respond to the influenza threat and were saddled with the worst rate of death among all cities in the United States.

Lawrence County was more fortunate and actually suffered relatively few deaths when compared to other areas. There were a reported 2,801 cases of the Spanish Flu in New Castle from October-December 1918, with 212 cases resulting in death. During that same period Ellwood City had a reported 1,543 cases with 48 deaths. The numbers can be deceiving because in Ellwood City another 69 people died from flu-related pneumonia or tuberculosis. The Borough of Wampum was probably the worst off in terms of percentage, suffering almost 900 cases of the Spanish Flu with a reported 37 deaths.

Getting an accurate worldwide count can be difficult, but modern research estimates that at least 50 million people – but maybe as many as 100 million – died from the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919. When it was all said and done it’s possible that about 6% of the world’s population had died. Just when and where the Spanish Flu originated is still debated today, but there is no debate that is was one of the greatest medical disasters of all time. It wasn’t until the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-2022 that the world witnessed anything even similar.

The first large outbreak of the Spanish Flu occurred in March 1918 at Fort Riley, a sprawling U.S. Army training facility located in north central Kansas. Over 1,100 soldiers fell ill and were hospitalized at Fort Riley (shown above). Similar outbreaks followed at other military bases and this has led many people to believe the flu was a product of the U.S. military’s biological warfare effort. In March and April 1918 as many as 202,000 American troops were sent to join the war effort in Europe. They carried more than their gear – they carried the Spanish Flu as well. (1918) Full Size |

|

A typical emergency hospital prevalent in 1918, this one on the porch of the U.S. Army’s Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. Isolation and ventilation were thought to be key factors in treating the Spanish Flu. Bed sheets were used as sneeze guards between the patients. This scene was commonplace throughout the world, as isolation wards were set up in hospitals, churches, factories, private homes, and other buildings. (1918) Full Size |

The emergency hospital setup on Church Street in Wampum in September 1918. Wampum, and surrounding areas like Crescentdale, Clinton, Coverdale, were hit hard by the Spanish Flu with a reported 885 cases – with 37 deaths. The Crescent Portland Cement Company also set up an emergency hospital for its employees. (1918) Full Size |

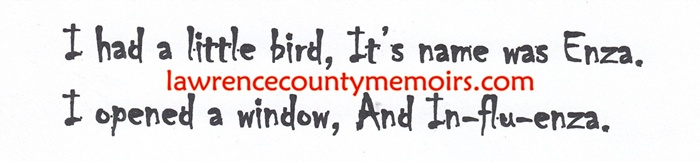

A popular children’s historical rhyme that originated during the time of the Spanish Flu epidemic in 1918. Full Size |

On Friday, October 4, 1918, Dr. Steen ordered that this notice be posted on all dance halls, saloons, wholesale liquor stores, theaters, and other public meeting places. Schools and churches were soon added to the list of places to be shuttered. This notice signaled the beginning of the first “flu ban” in New Castle, which lasted until November 10. (1918) Full Size |

The sleepy village of Hillsville, Pennsylvania, blossomed in the early 1890’s when Italian and other European immigrants began flooding into the area to work in the numerous limestone quarries. Many of these immigrants were from the region of Calabria in southern Italy, an area where limestone quarries were also in abundance. The Italian community in the vicinity of Hillsville, as was typical, featured tight-knit families with strong Catholic values. Of the almost 1,500 people residing in Hillsville in the early 1900’s, about 900 of them were Italians. The majority of the Italians were honest and hard-working laborers, but a handful of them were formerly associated with crime syndicates in southern Italy.

Before too long the Italian community in Hillsville, and those in the neighboring locales of Bessemer and Carbon, came under the control of a group of feared Italian enforcers generally known as “The Society.” The Society exercised great influence and essentially ran all aspects of the Italian community. They acted as a liaison with the quarry owners, headed up the religious councils, controlled alcohol and retail sales, regulated all forms of criminal activity, and settled disputes within the community. All working Italian men were expected to pay “dues” in exchange for protection.

When met with resistance the Society’s main weapon was to extort money. One of their favorite forms of extortion was known as the “Black Hand,” sending a letter – usually signed with a dagger, a black hand print, or another sinister symbol – threatening the recipient to bring money to a drop off location or face violent reprisals. It was this form of extortion that led the press to eventually dub these Italian crime syndicates, which operated in most Italian communities across the country, as the “Black Hand” or “Black Hand Society.” Most of the poor Italian immigrants complied as most spoke no English, wanted to avoid trouble, and were unaware of how to seek outside assistance. Many workers simply left the area and this trend worried the quarry owners.

In 1905 the Black Hand Society in Hillsville was led by forty-year-old Rocco Racco, who hailed from the town of Grotteria in southern Italy. Racco, who spoke decent English, had been in the country for almost two decades and had resided in Hillsville for about six years. Racco owned and operated a general store with his wife Maria and the Italians under his protection were all expected to shop there.

A strike by quarry workers in late 1905 and other factors led to a violent power struggle within the Black Hand Society in Hillsville. Two of Racco’s rivals, Ferdinando “Fred” Surace and Giuseppe “Joe” Bagnato, banded together and basically forced Racco out of power by the spring of 1906. Surace became the new leader of the group, but violence prevailed throughout the remainder of the summer.

Add to the mix a tense rivalry involving landowners, the Pennsylvania Game Commission, and Italian immigrants. With the influx of immigrants in the late 1800’s many longstanding landowners in Pennsylvania grew to resent foreigners, who often trespassed on their lands while hunting birds and other game. Tensions were volatile and as a result the Pennsylvania Game Commission was founded in 1895 to begin overseeing the conservation and management of wildlife. It wasn’t long before the Game Commission began targeting Italian immigrants as the main violators of state game laws. The poor Italians, surviving on a minimum wage, could afford neither the license fees nor the stiff fines. Landowners were pleased, but Italians generally grew to hate the Fish and Game Wardens.

L.S. “Seeley” Houk, the Fish and Game Warden for Lawrence County, yielded considerable power while aggressively enforcing the state game laws. Seeley Houk – also given as Seely and Sealey – was a mean and fearless man who was not afraid to boldly challenge poachers and other violators. He was known for his mistreatment of foreigners and a handful of complaints were lodged against him. In August 1905 he was convicted of assaulting an Italian, but the sentencing was delayed until late March 1906.

In February 1906 a determined Houk, who continued in his duties, encountered an Italian who he believed was illegally hunting near Hillsville. A dispute arose and Houk shot the man’s dog. The hunter escaped and fled back to Hillsville. Unfortunately for Houk, it turned out that the animal was Rocco Racco’s prized hunting dog.

Not long after, on Friday, March 2, 1906, Houk disappeared during a regular inspection trip to Hillsville. Speculation was that he fled to avoid being heavily fined or even sent to jail in his upcoming sentencing trial. An investigation by local authorities turned up nothing and his whereabouts remained a mystery. An arrest warrant was issued on March 24 after he failed to appear in court for his sentencing hearing.

A month later, on Thursday, April 24, 1906, a Pennsylvania Railroad crew spotted a body floating in the Mahoning River near Hillsville. The crew continued on towards New Castle where they alerted the police. Authorities descended on the scene and before long it was determined that the remains were those of Houk. The body had been carefully weighted down with rocks, but an unusually low tide had revealed its presence. The New Castle News of Friday, April 25, 1906, reported, “An examination of his body by Coroner Cox, Thursday afternoon, and a postmortem held later in the evening, revealed ghastly wounds about his breast and head, indicted by a shotgun in the hands of some unknown person or persons. Blows, probably delivered by a club or a foot, supposedly after the shot had been fired, horribly mutilated the victim’s face and head. The body of the murdered man was almost beyond recognition.”

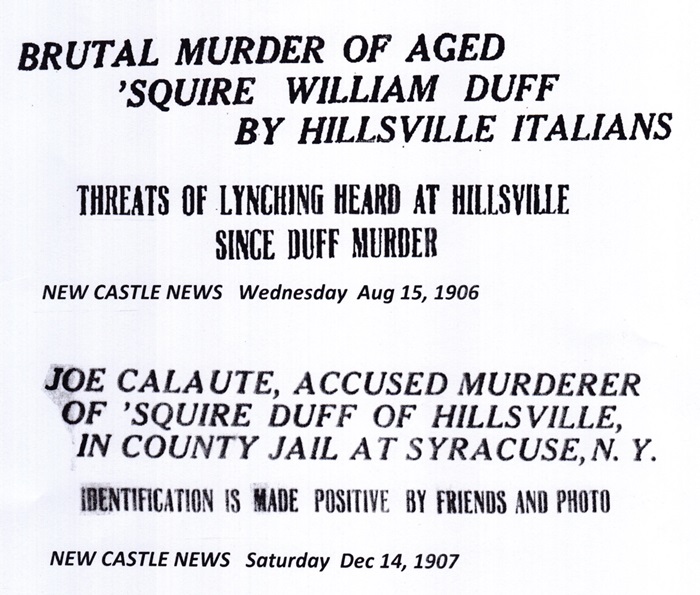

Local authorities went to work on the case but made little headway. Residents of Hillsville remained tightlipped, and the investigation quickly stalled. A few months later, on the afternoon of Monday, August 13, 1906, eighty-year-old farmer William “Squire” Duff heard someone shooting on his property near Hillsville. He went to investigate and was greeted with a shotgun blast to his face. Duff initially survived but passed away the following morning.

The news of Duff’s murder quickly spread and public outrage ensued. On Wednesday, August 15, 1906, the New Castle News reported, “One of the most wanton of the long list of murders that has disgraced this county was perpetrated when ‘Squire William Duff of Mahoning township, one of the oldest and most respected residents of the county, was mortally wounded in the most unwarranted manner.” A funeral was held in Hillsville on Thursday, August 16, and Duff was laid to rest in the Hillsville Cemetery.

Italians in Hillsville, unlike their response to the Houk murder, began to talk freely about the Duff case. Two Italians, Joseph Calauti (or Calaute) and Dominic Sainato, were quickly identified as suspects with Calauti believed to have been the shooter. A manhunt got underway to locate Calauti, but the New Castle News of Wednesday, August 22, 1906, reported, “All efforts to locate him have failed. Posse’s have scoured the country in the vicinity of the murder and for miles around, but in vain. Calacti is missing as though the earth had opened and swallowed him.”

Local authorities and the limestone quarry owners banded together and soon hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to assist in the crusade against the Black Hand Society. Pinkerton agents began using informants to develop leads in the murders of Houk and Duff, but also of Black Hand activities in general. A handful of undercover agents of Italian descent moved into Hillsville and began working in the limestone quarries. One Pinkerton man, known as Operative #89, even managed to infiltrate the leadership of the Black Hand Society.

Meanwhile, Rocco Racco was charged and convicted of minor theft in September 1906. While out on bail pending formal sentencing he skipped town. Racco was captured by County Detective J. Lee McFate in New York City two weeks later and was returned to New Castle. He was sentenced to fifteen months confinement and sent to the Western Penitentiary in Pittsburgh. The investigation against the Black Hand Society continued in earnest.

In January 1907 a new crop of county officials assumed office, including District Attorney Charles H. Young, County Detective Creighton G. Logan, and County Sheriff John W. Waddington. These men picked up and case and finally, in the summer of 1907, authorities were ready to strike. On Saturday, July 13, 1907, hundreds of Italian quarrymen lined up to get their pay at the train station in Hillsville. Twenty-two of the men were told there was an issue with their pay and to come back into the office to straighten it out. One by one those men were placed in handcuffs and told to keep quiet. Before long a host of lawmen and undercover Pinkerton agents swarmed from hiding and secured the entire area. The twenty-two men were loaded aboard a train and rushed to the county jail in New Castle. The operation was carried out with flawless perfection.

Many other Black Hand members, including those in the upper echelon, may have been tipped off and fled the area. Surace escaped to upstate New York, where he was arrested and returned to New Castle a month later. Bagnato absconded with $11,000 in extortion money and disappeared back to Italy. Salvatore Candito (or Sam Kennedy), who briefly took over command, fled to New York but was captured near Ellwood City a month later. Other suspected members were also arrested in the coming months, and all were prosecuted over the next year or so. Most of the men were convicted, with some receiving sentences of up to ten years in prison.

On Saturday, December 28, 1907, as Racco was released from the Western Penitentiary, police officials from Lawrence County were on hand to arrest him. He was brought back to New Castle to face charges regarding his involvement in the Black Hand Society. The following May, after developing a case and gaining key witnesses, Racco was formally charged with the murder of game warden Seeley Houk.

His murder trial, sensationalized in many newspapers, commenced on Tuesday, September 15, 1908. Racco, represented by attorneys Harry K. Gregory and Archie W. Gardner (and later by Samuel P. Emery), swore his innocence and maintained he was being framed. Among the key witnesses against him were Black Hand members Ferdinando “Fred” Surace, his main rival, and Dominic Sainato, recently convicted in the killing of William “Squire” Duff. They both received lighter sentences – Surace received ten years and Sainato received twenty years – as a result of their testimony. Sainato probably avoided the death penalty by testifying against Racco.

The two men testified that Racco had confessed to them about killing Houk. The story goes that Racco and his brother-in-law Jim Murdock (or Vincenzo Murdocci) hid in a wooden area along the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks on the south side of the Mahoning River near Hillsville. They ambushed an unsuspecting Houk, shooting him in the face with a shotgun and then beating him unmercifully. The two assailants fled the area but returned later that same day. They weighted Houk’s body with rocks and tossed the remains into the Mahoning River. The motive for the murder was said to be revenge in response to Houk shooting Racco’s hunting dog, but it was also theorized that Racco – in a battle to retain command of the Black Hand Society – killed the Game Warden to demonstrate his power.

Among those who testified was Italian immigrant Fred Rosena, a fellow inmate at the County Jail who was awaiting his own trial for murder. The New Castle News of Wednesday, September 16, 1908, reported, “A sensational feature of the trial Wednesday morning was the testimony of Fred Rosana (sic), who is in jail for the murder of his brother-in-law. Rosana contradicted the testimony which he had given before Alderman Green. He said there that Racco had threatened Houk’s life but in court claimed Racco said he would kill the man who killed his dog. When asked why he changed his story he said that Racco had threatened to kill him in the county jail for testifying as he had done before the alderman.” Rosena went on trial in December 1908, was sentenced to death, and executed in December 1909.

The testimony concluded on the afternoon of Saturday, September 21, 1908, and the jury took to its deliberations at 3:00pm. It took only two hours for a verdict to be reached. Racco was led back into the courtroom to hear the verdict. The New Castle News of Monday, September 23, 1908, reported, “’Once to be born; once to die’ – Rocco Racco. With the gallows looming up before him and the verdict of the jury, ‘Guilty of murder in the first degree,’ ringing in his ears, Rocco Racco made the above comment on his way back to his gloomy cell.”

Not surprisingly, Racco was convicted of the murder on purely circumstantial evidence. Unfortunately for Racco his brother-in-law Murdock had long since fled to Italy. In March 1909 a hearing was held in New Castle and Racco was sentenced to die by execution. A few months later Pennsylvania Governor Edwin S. Stuart set the execution date as September 23, 1909, but it was soon delayed a month.

Racco’s attorneys filed various appeals, including one with the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, but all were denied. A review of the facts casts some doubt on whether Racco actually killed Houk. It seems likely that the testimony against him was coerced and fabricated to some degree. A more plausible scenario is that Murdock actually killed Houk, although Racco probably ordered the “hit.”

During the appeals process, Racco awaited his fate while confined in the Lawrence County Jail. A notice was posted in the New Castle News of Friday, October 8, 1909, that read, “Notice is hereby given that Rocco Racco will make application to the Board of Pardons on Oct. 20, next, for a commutation of the sentence of death to one of life imprisonment. S.P. EMERY Attorney for Rocco Racco.” This measure was soon denied as well.

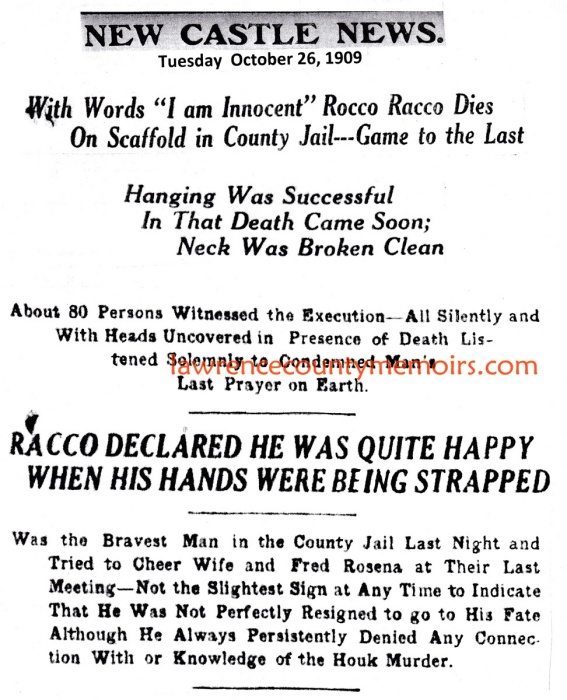

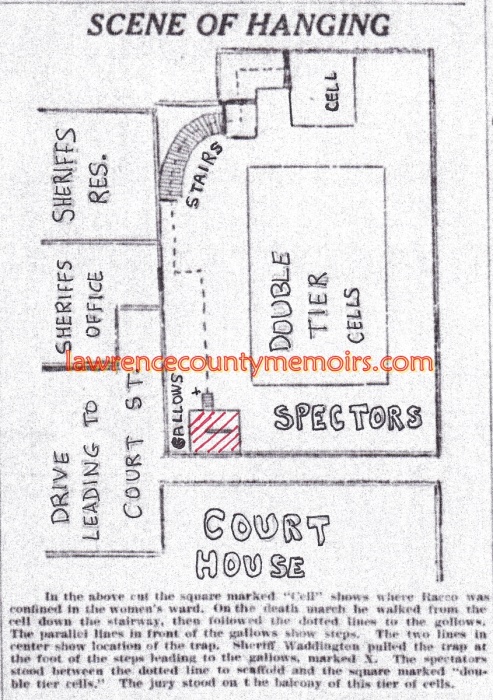

On the morning of Tuesday, October 26, 1909, Racco was led to the gallows in the jail courtyard where about eighty people were assembled to witness the execution. Just about 10:30 am he made a brief statement proclaiming his innocence. Newspapers across the country reported on the event and the Titusville (PA) Herald had this to say, “Without fear and expressing his forgiveness for all the officials, Rocco Racco, a well-known Italian, alleged leader of a black hand organization, and convicted of the murder of Selee Houk, a state Game Warden, a year ago, was hanged in the county jail yard here (New Castle) today. On the gallows, Racco said: Gentlemen, I did not see Selee Houk killed; I did not see anyone kill him and I have no suspicion of any person. I pardon everyone and expect to go to Jesus right now. Good bye.” Racco was blindfolded and then nodded to Sheriff John W. Waddington, who pulled the lever to open the trap door. Racco’s neck was snapped and he was pronounced dead at 10:40am. His remains were reportedly buried in an unmarked grave in the St. Lawrence Cemetery in Hillsville.

In early 1922 the fugitive Jim Murdock was back in the news as he apparently made a re-appearance in Lawrence County. The New Castle News of Thursday, February 15, 1922, reported, “It is possible that, in a very short time, Jim Murdock, wanted here for being an accomplice in the murder of Seely Houk in 1906, may be apprehended and forced to stand trial. Murdock is a relative of the late Mrs. Rosa Deln who was burned to death near Edenburg a few days ago. It was learned that he intended to be at the funeral and a guard was stationed near the church. In some way Murdock learned of the presence of the guard and fled in the middle of the funeral service.”

Two days later the New Castle News printed a statement released by County Detective Jack M. Dunlap, known for his aggressive pursuit of bootleggers during his 1922-1925 term, that read, “No statement was ever been made to any one that an innocent man was hanged for the murder of Seeley Houk. The stories carried in other papers were written from the information made against Jim Murdock in a local alderman’s office. I made the information at the instance of former officials who were interested in the Rocco Racco case. I was informed that Murdock was wanted as an accomplice of Rocco Racco. I have not at any time said that an innocent man was hanged for the murder of Sealey Houk and I have no information that would lead me to be of this opinion.” Jim Murdock apparently evaded capture and was never brought to trial for his involvement in the murder of Seeley Houk.

Many accounts also indicate that Hillsville native Joseph Calauti, believed to be involved in the murder of William Duff, disappeared and was never brought to trial. However, that is not entirely true. Calauti remained elusive for many months but was finally located in December 1907. He was found to be serving an eight-month sentence in the Onondaga County Jail in New York. He had been arrested the month prior for carrying an illegal revolver. In January 1908 he was returned to New Castle and formally charged with the murder of William “Squire” Duff. In June 1908 his charges were dropped and he turned state’s evidence to be the key witness in the trial against Dominic Sainato. Calauti claimed he was present (but unarmed) at the murders of Seeley Houk and William Duff, and his testimony helped convict Sainato. Calauti was released from custody in early July 1908, though lingering doubts about his innocence persisted for many years.

The Black Hand Society in Hillsville was severely crippled by the trials of 1907-1909 as most of its members sent to prison or fled to avoid prosecution. The law-abiding residents of Hillsville were then generally free to live more normal lives. The Black Hand gangs continued their criminal activities in other locales, particularly New York City, and eventually formed what became known as “the Mafia.”

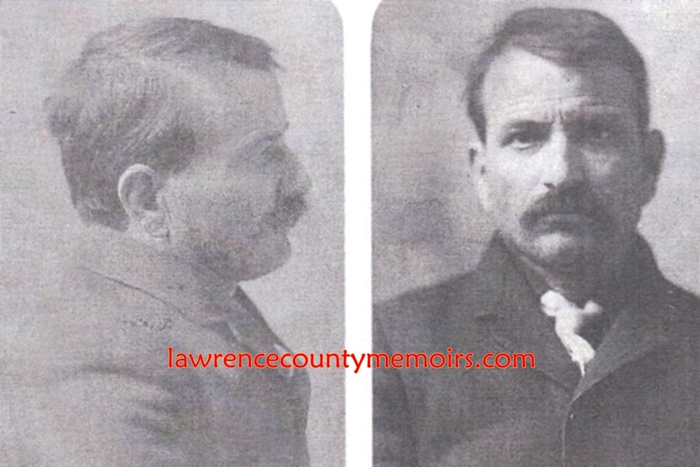

Racco’s sensational trial, which saw him convicted of murder in October 1908, was one of about fifty undertaken in New Castle to crackdown and eliminate Black Hand activities in the region. Racco was hanged to death in New Castle in October 1909. His accomplice Jim Murdock escaped capture and possibly fled to Italy. (1908) Full Size |

|

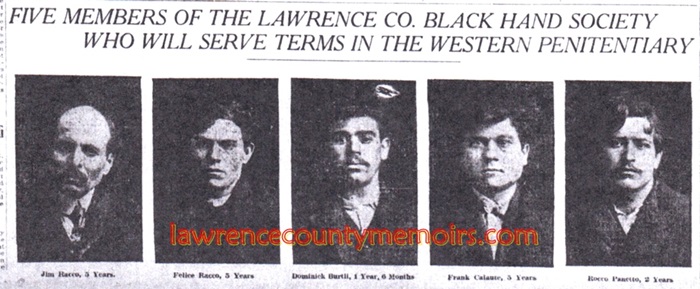

In June 1907 five well-known members of the Black Hand Society were sentenced to prison for various crimes ranging from selling illegal liquor, robbery, conspiracy, and carrying a concealed weapon. Three of these Hillsville men received sentences of five years’ incarceration. (1907) Full Size |

|

The death certificate of “Roco Racco,” which lists his cause of death as “Came to his death from hanging by the neck until dead.” (1909) (Courtesy of R. Rangel)Full Size |

|

|

Rocco Racco is buried in an unmarked grave somewhere within the confines of the St. Lawrence Cemetery in Hillsville. (May 2014) Full Size |

In early 1926 a small enclave of Ukrainian immigrants in New Castle, Pennsylvania, decided to form their own Orthodox church. These majority of the Ukrainians, who had been immigrating to the United States since the 1870’s, had previously been attending services at St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Catholic Church on East Reynolds Street. They met in a private home in February 1926 and organized what became the Holy Trinity Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The new church aligned itself with what later became the New Jersey-based Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the United States of America.

They took up donations and soon purchased a lot on Rose Avenue, where it intersects Stanton Avenue. They borrowed additional funds and soon started work on a small church. On Sunday, October 3, 1926, the church was dedicated during a ceremony in which the cornerstone was laid. The New Castle News of Friday, October 1, 1926, reported, “The dedication services will be in charge of the pastor Rev. Ch. Yacobchuk, Rev. Gregory Clemovich of Butler, Pa., Rev. Koshel of Youngstown, O., Rev. Sidlecki of Ambridge, Pa., Rev. Kashuba of Pittsburgh. The Ukrainian National chorus of Youngstown, O., will furnish the music for the occasion.” Subsequent services were primarily held in Ukrainian – with one a month mass provided in English.